|

|

|

|

River of Life - Bear Creek, Colorado March 3, 2021 Photos and text by Dave Parsons Walking on a cold winter day, I stopped for a minute to watch the dark-eyed juncos and finches flit about in the nearby shrubs. The sun was out and all the birds were quite chatty including a squawking blue jay. Suddenly, a flock of finches and a few pigeons flew past a tall cottonwood towering over me. The juncos dove into the heart of the shrubs. I turned around just as a diving, light colored rock pigeon swerved feet in front of me and towards the willows with a large Cooper’s hawk hot on his tail. With fully outstretched wings, she banked hard and fast to follow her prey with a loud swoosh. All the bird chatter was silent as the pigeon folded his wings and dove in the thick willow bushes near a gurgling creek. The hawk swerved effortlessly up to a perch, quickly landed and folded her wings in a nearby cottonwood tree branch over the creek about 20 feet from the pigeon. I stayed put watching the chase unfold.

Still focused on her target, she moved her head from side to side and up and down, as the hawk adjusted her position in the tree. After a couple of minutes, she lifted off the branch and glided into the thick willow branches folding her wings at the last moment before the collision, only to be repelled by the tangle of twigs. She awkwardly turned with outstretched wings for balance and jumped onto a willow branch over the water. Close to her prey now, the hawk again dove into the willows. The pigeon scrambled through to the other side and flapped loudly into the air. Jumping after her escaping prey with a wobbly takeoff, the hawk followed the pigeon into a nearby set of pine trees, hopping from branch to branch and down behind a wood fence. Out of sight now, I walked to where I last saw the two disappear and watched three light colored feathers silently float down into the cattails. Standing quietly, I listened and looked for any sign of movement, but all was quiet. No birds flew out from behind the fence and the only sound was gurgling water passing over the rocks and reeds.

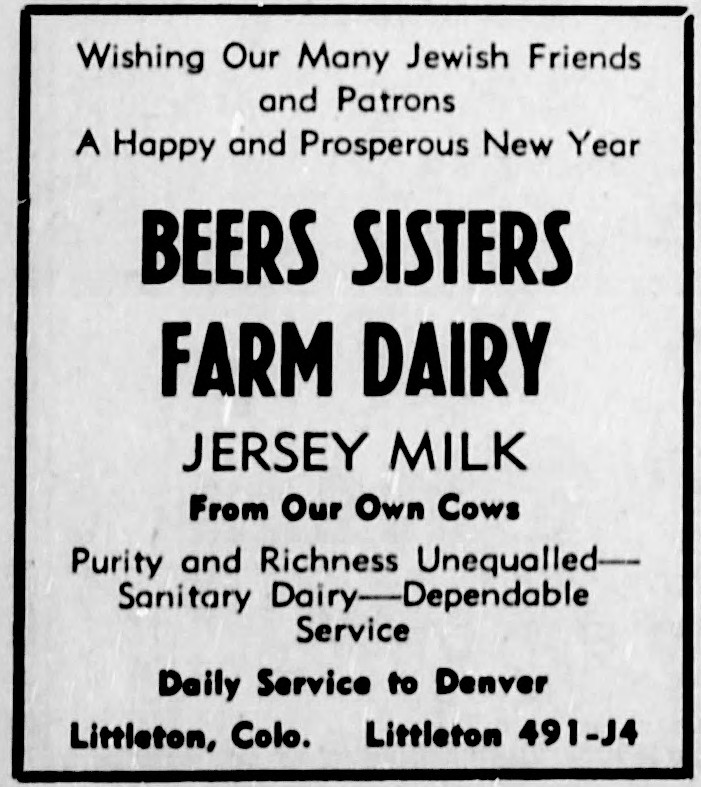

Still used today, the Arnett-Harriman Ditch completed on April 15, 1868 (had priority No. 19 brought from the Robert Lewis Ditch completed October 1, 1865 - Lakewood Colorado), flows out of Bear Creek as it emerges from the Rocky Mountain foothills at the small town of Morrison, Colorado. The ditch fills numerous reservoirs as it winds like a snake across the landscape including the nearby Harriman Reservoir. Flowing past hills and homes, the waters of Bear Creek have for millennia created diverse wildlife hot spots while sustaining an ever growing Colorado population. Following the curving contours of the land, the path of the irrigation ditch wanders eastwards. Eventually, the Harriman Ditch approaches the busy, four lane West Belleview Avenue, once a dirt wagon road named the "Beers Sisters Road" into the 1950s. An anomaly at the time, shunning both marriage and childbirth, The Beers Sisters, Mattie, Edna, Bessie, Marguerite and Ollie were strong women who created a successful family dairy farm nearby in the 1920’s. Once cheated by unscrupulous middle men, the sisters carved out their own complete dairy production line from hayfield to home delivery. Using funds from earlier, hard won agricultural successes, they purchased their own land from Charles Bowles and astutely litigated water rights from the Harriman Ditch for irrigation. With an enduring work ethic, they daily hoisted 100-pound milk cans, planted and raised over 480 acres of crops and milked over fifty Jersey and Guernsey cows, twice a day - by hand. They built a bottling plant, purchased delivery trucks and hired drivers, fed and cared for the cows and built a highly successful wholesale dairy business, the Beers Sisters Farm Dairy, with delivery of milk, butter, cream, eggs and honey.

Running parallel to Belleview, the Harriman ditch changes it name to the Bowels Lateral, named for another early 1860’s Colorado pioneer. Used to fill Marston Lake in the early 1900s, the ditch today provides water for Jeffco Public Schools, Fort Logan National Cemetery, Pinehurst County Club and other nearby areas. Flowing eastwards, the water passes a large open field which is filled with alfalfa. Last summer, as forest fire smoke blanketed the front range, I watched a Swainson’s hawk floating on the wind over the field. He gradually glided down to a tall cottonwood perch. With ease, he snipped off a nearby branch using his beak like pruners. Holding the branch in his beak, he stretched his wings and took off, passed the branch to his talons in midair and drifted off to the neighboring tree without flapping once. Gently landing, he worked and wove the branch into his growing nest as his mate circled high above, enjoying the windy day. Down below the trees, fluttering around the tall grass, a rusty colored, queen butterfly landed on a milkweed leaf to sun and warm herself in the smoky air.

Tiny, thumbnail sized brown skippers, intricately patterned marine blues, and yellow sulphur butterflies drifted around the small islands of alfalfa flowers lining the waterway. Red and pink milkweed beetles with long stripped antennae munched on sticky milkweed leaves as the occasional bright orange monarch butterfly drifted by. Colorful, hand sized, yellow and black stripped tiger swallowtail butterflies flew around the tree tops along the ditch. Endlessly darting around tall blades of grass here and there, a tiny grey hairstreak butterfly, with dangling feathery tails, finally landed on a purple alfalfa flower. Feeding with his antenna down, wings folded back vertically, he shuffled his hind wings with orange eye spots back and forth, his disposable black and white "antenna" tails drawing the attention of any potential avian predator away from his tiny body. Once or twice a week, a pair of coyotes makes the rounds, marking their paths with their last digested meal. They regularly patrol this stretch of the field, trotting along the tree line for camouflage and cover. Sometimes very bold, the pair will walk along the opposite side of the creek where they track oblivious dog walkers engrossed in their phones or conversations. Watching, with their glowing, black outlined eyes, they warily follow the human movement as they trot past in the opposite direction or just stand still. Most times, the people see nothing. Sometimes, If walkers are present, I will point out the nearby predator in the tree or on the ground. Throughout the year, hand written signs posted on nearby lamp and fence posts occasionally pop-up picturing lost small dogs and cats, usually the size of a healthy meal for a passing coyote.

Walking through a tunnel of trees walled in by a six-foot fence and the water, I regularly encounter garder snakes sunning themselvers on the trail in the summer. Further along, the path opens up to another green space. Chirping continuously, emerald green and shimmering broad-tailed hummingbirds compete with one another in high speed chases in between tall trees while families of noisy, bug hunting house wrens chitter away with an occasional, hidden, spotted towhee shuffling in the fallen leaves under a shrub. Downstream, flying in an almost invisible pack, over twenty, tiny, gray bush-tits pounce on poplar, devouring sappy leaf munching aphids while subtly squeaking their high pitch chirp. Standing underneath the tree, black-capped and mountain chickadees join in the feast, hopping just a few feet overhead from branch to branch enjoying the sugary protein packets. At the same time, black and white translucent winged dragonflies and small blue damselflies enjoy hunting over the water while busy robins feed their noisy, fluttering chicks.

In the past couple of years, nesting in the old cottonwoods near the ditch, Cooper’s hawks have been very successful hunting and raising large families. Last year, they raised four chicks and for many June days, young hawks would line up on a tree branch, constantly screeching when the adults were nearby. After flying off, the chicks would quiet down and walk around on the branches and many times regroup on another tree or fly off in separate directions. On hot days, they would all drop down to the same spot in the creek one by one and take a drink or a bath. One fall day near the cattail filled wetlands, I stopped to watch a red tailed hawk perched in a cottonwood tree. Turning his head towards the field, the hawk slid off the tree and glided down, diving into the tall grass. Coming up empty, he looked around, took a few awkward steps, leapt into the air and with ease, calmly flew five feet in front of me up to another lookout high in the tall cottonwoods. Enjoying the moment, I continued my walk crossing the wooden bridge over the now dry creek bed. Once again, wary coyotes regularly trot down this section of the creek, charging at mallard ducks and patrolling the edge of the reeds. Raccoon tracks are regularly pressed into the mud lining the bank. Frequently, leaving a soft, fluffy, white tails and a few tufts of gray fur blowing in the grass, red-tailed hawks dine on a cottontail rabbits while perched on a cottonwood branches over the creek. Also hunting in the nearby neighborhood, hawks will jet down from above and pounce on the unwary cottontail rabbit dusting themselves in a dry lawn or feed on a unsuspecting finch under a window.

Great horned owls also enjoy the numerous lookouts and fields for hunting along the ditch. In the evenings they will hoot back and forth to each other as white and red breasted nuthatches along with black capped chickadees and downy woodpeckers happily patrol the nooks and crannies in the numerous rough bark of pines and poplars. Many times the owls will perch on the branch above the path allowing pedestrians to walk close by underneath. And again, most people engrossed in their own world simply walk by the unseen and unknown nature they live in.

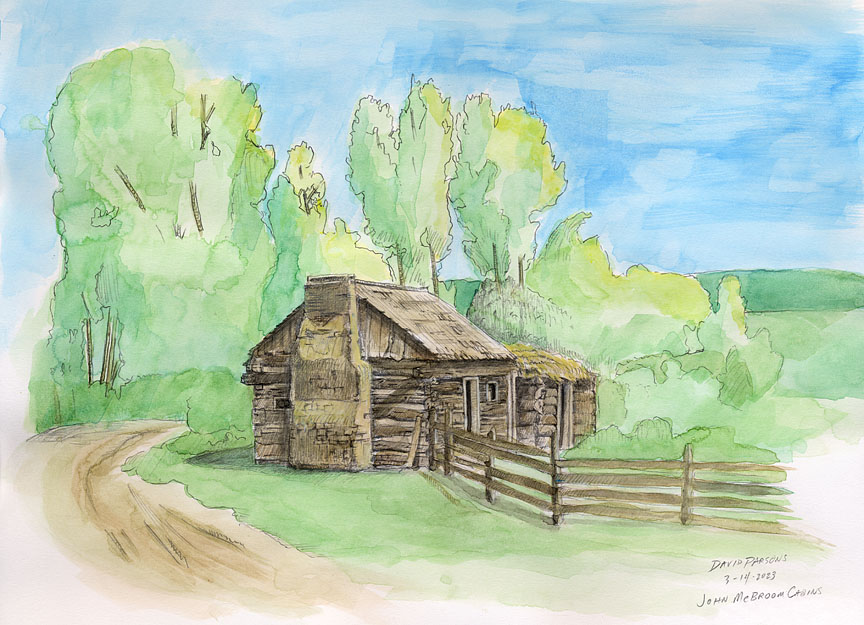

On a warm, spring day riding my mountain bike northwards, I rolled over the wooden bridge past the flowing waters of the ditch and around the wetlands filled with noisy red-winged blackbirds jostling for position in the cattails. Passing the 1970’s built park and homes, I turned towards the west and pedaled on a dirt path past recently constructed, ridiculously tightly packed, two story homes that now stand where a historic farm once stood for over 100 years. The old homestead and even older barn stood near a small lake, Stickford Lake, once filled by the waters of Bear Creek running through the Harriman Ditch. Over time, sediment filled the lake and it would only hold water after heavy rains or snow storms. Developers finished the job permanently, grading over the entire farm without a second thought. With the relentless pace of development, demolition and construction moved at such a fast pace, county historians didn’t have a chance to fully document the pioneer architecture of the farm.

Back in the 1880's, Stickford Lake was filled with fish and the 160 acre farm was a mile long and quarter mile wide and covered with crops of clover, timothy, upland hay, oats and wheat. There was 25 acres of apple trees, as well as smaller gardens of raspberries and strawberries. Shade trees surrounded the Stickford family house. According to a May 3, 1893 newspaper, The Colorado Transcript, it was "one of the choicest small farms in the county." Now, it’s a cookie cutter constructed neighborhood designed for maximum profit an minimal green space, the only park, a grass filled water drainage area with a few picnic tables, swings and a small playground around the dry edges. Ironically, as I watch the open spaces near my home filled in with poorly designed and mindless development, I can only imagine what the early Native Americans felt as Europeans descended like a plague of locust devouring the county, consuming the land for it’s mineral wealth, timber, and wildlife.

Once a lonely gravel lane called "Bear Creek Road," the busy six lane suburban superhighway now known as South Kipling Street runs north and south in front of Harriman Lake Park. Letting the street light to change to red, I crossed the raised median into the gravel parking lot to the relative safety of the park. Popular with dog walkers and runners and a Colorado birding hotspot, I pedaled the dirt road around Harriman Lake past more flocks of red-winged blackbirds as they noisily nested in the thick cattails surrounding the water. Another favorite haunt for nesting great horned owls, the tall cottonwood trees that surround the lake also provide nesting niches for northern flickers and tree swallows. Along the shoreline, cliff swallows gather mud as plovers and sand pipers pick off insect pests. Every kind of water bird, dabbler, diver, merganser, grebe and heron enjoys hunting in the waters while raptors circle the shorelines and grasslands in the park. Muskrats weave through the reeds and paddle from shore to shore with their tails moving like little motors. Bald eagles regularly strafe the nervous flocks of Canadian geese paddling around the shallows or perched precariously on the ice. Migrating tundra swans have visited in the fall while warblers and loons pass through in the spring.

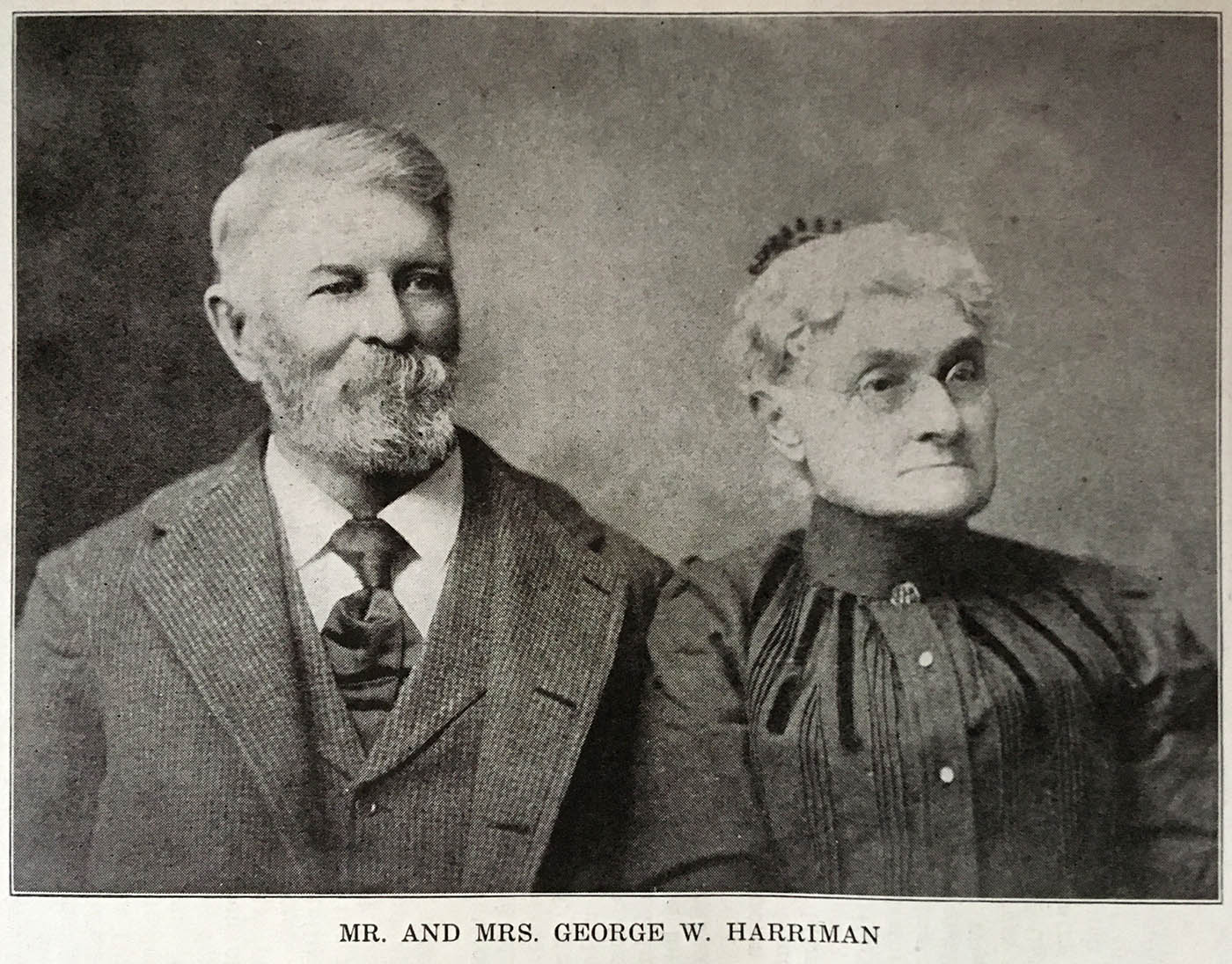

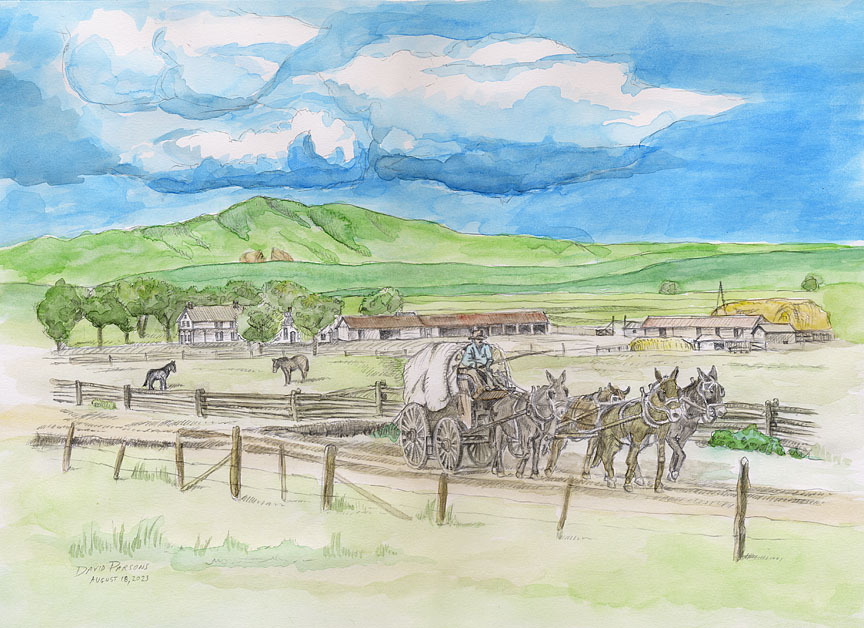

In the past, even full grown bull elk have wandered through the willows along the waters edge. Families of coyotes hunt along the lake shores, often venturing out on the frozen ice in the winter. Pedaling west towards the mountains, the dirt road then curves northward as I pass the rocky, reservoir dam and spillway where more cliff swallows gather up mud for their adobe homes. The dam was replaced in 2013 by Denver Water after two years of construction, replacing the aged and silted-in 138-year-old dam and bringing the reservoir up to its full water storage capacity. Just north of the dam a couple hundred yards, Harriman built his ranch homestead complete with barns, corrals and herds of horses and cattle. In 1860, he arrived in Boulder, Colorado with a two horse team and tried his hand at running a mountain hotel and stage line in South Park. Ten years later George Washington Harriman homesteaded 160 acres overlooking the Bear Creek Valley. Later expanding his ranch to 880 acres, he completed his ditch and built the reservoir in 1873 which still bears his name. He is known to Colorado historians as "the father of the great system of storage reservoirs," after building the first large scale reservoir in Colorado. Harriman also served on the board of County Commissioners for city of Golden, but always kept working to improve his irrigation and reservoir system for the growing population of the area.

Harriman was also instrumental in building one of the early roads just west of his ranch. Along with five other partners, they incorporated the Denver, Turkey Creek and South Park Road Company in 1865 and helped construct the Turkey Creek Road along with John Parmalee and his son Clark (of Parmalee Gulch in the Indian Hills).

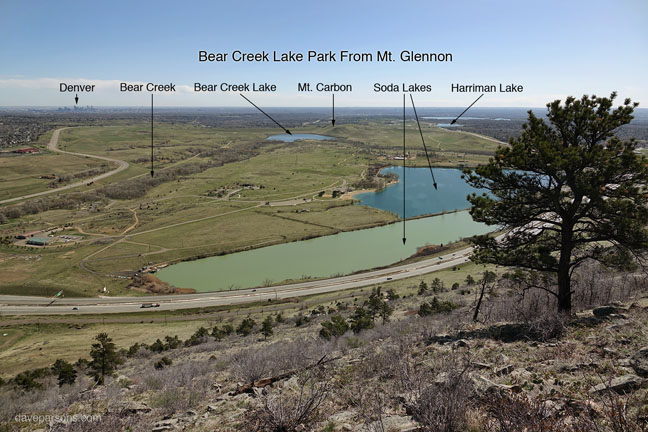

In 1891, Harriman organized the Harriman Ditch Company acquiring the Arnett (Harriman) Ditch and its property rights which consisted of the 1868 built ditch from Turkey Creek and the original 1869 construction of the Bear Creek Ditch. Later, Harriman created The Soda Lakes Reservoir and Mineral Water Company to build the two Soda Lakes outside Morrison in 1893. Afterwards, Harriman and his companies with their various shareholders worked with early variations of Denver Water to supply water to not only the farmers and ranchers near Harriman Lake, but to the Denver metro area as well by providing water to Marston Lake which was constructed in 1900.

Rolling past the Harriman Lake dam, across Quincy Avenue or "Prison Farm Road" during the 1950’s and the nearby Federal Prison, I pedaled by the area now known as Fehringer Ranch Park, named after a later settler who acquired the Harriman Ranch. Now, solid, compact frisbees freely fly by where horses and cattle once grazed. Celebratory cheers can be heard as discs collide with clinking chain targets as dedicated Frisbee-golf or disc-golf players wander the dusty, 18 hole course on the 135 acre site in all weather conditions. Target baskets and tee pads now stand where the barns, crops and corrals once stood on the Harriman Ranch. According to The Colorado Transit in September of 1893, along with his ranch co-owners ex-Governor Grant and S . B . Morgan, Harriman managed the farm that consisted “of fifteen hundred and twenty acres, of which two hundred are in alfalfa, one hundred and sixty in wheat, forty in oats, forty in clover and timothy, the balance is whole pasturage land but the whole will be cultivated next season. The threshing is nearly finished: wheat averages twenty bushels, oats, thirty; there has been made two cuttings of alfalfa which averaged a ton and a half each cutting.” Today, it’s a rare piece of land still free of homes along the Front Range. Despite becoming a dumping ground for cement slabs, dirt piles and landscaping debris, the site is busy with disc-golf players and wandering trails through prairie dog towns and meadows.

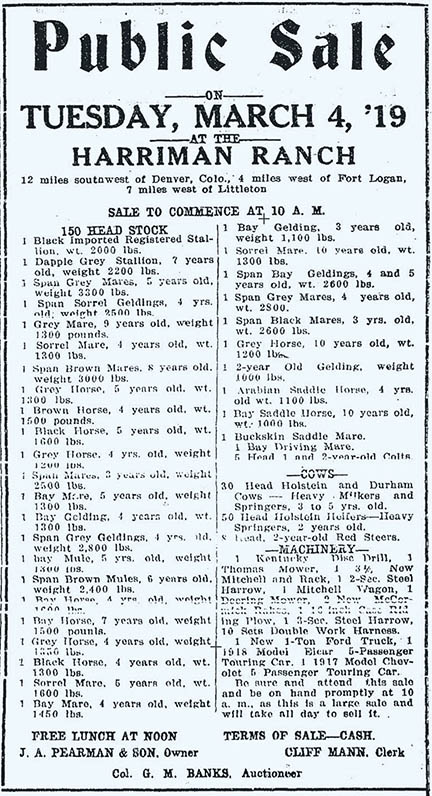

At 71 years of age, Harriman sold off his portion of the ranch in 1897 and the area passed through the hands of business partners, fellow ranchers and eventually Denver Water Union. As the property and possessions changed ownership, numerous auctions popped up around the 1920s as Harriman spent his last days living a few miles to the east in the town of Fort Logan from 1897 until his death in 1915. During the 1930’s, the property became a contentious subject for nearby farmers and ranchers as water rights and taxation became growing issues while the City of Denver sparred with Jefferson County. Fortunately, today, green grasses grow freely on the ranch, as Weaver Creek intermittently runs with water past the willows and cottonwoods providing hunting grounds for the ever present coyotes, hawks and great horned owls. The Rocky Mountains rise up in the west with Mount Morrison, Mount Falcon and Mount Glennon overlooking the Bear Creek Valley, Fehringer Ranch and Harriman Lake. Rolling away from the ghosts of Harriman Ranch, a herd of grazing horses napped and enjoyed a roll in the dirt west of Fehringer Ranch. Now pedaling up hill, I passed a spot where a dusty wagon road crossed in 1859. The old Bradford Road was a territorial "highway" in 1862 running to the southwest towards the Bradford house and its treacherously steep toll road into the Rockies. I pictured tired horses pulling creaky and rickety wagons with trail weary, dust covered pioneers up to the mountains, anxious to begin their fruitless search for elusive silver and gold. "On the Mt. Carbon road the teamsters would go together, so as to double each other out of a hole. One of our boys in a wagon had only a single team and he was pretty well behind. I was ahead with four horses and two wagons. You had to load them light, so they wouldn't sink. One wagon wouldn't take all you could put on it at that time. If you put all on one wagon you never would get to town. This fellow with a single team was stuck. Couldn't go no place. We put on four horses and we couldn't pull it. We put on twelve head and we couldn’t pull it. We put on four head more and pulled the wagon in two. The hind end stayed there and we had to dig it out with pick and shovel out of that old muck and stuff. Yesiree, we had to do it! We unloaded all his lumber and then couldn't get the gears out. It just cemented around them wheels, you know. We pulled the thing out and got it propped up and put his lumber on for him. We got to Midway that night, seven miles further on into Denver." (Wagons West - Lee Heideman) Pedaling the hill towards Mount Carbon, I crossed the bridge over Highway 285. I looked back as the sun reflected off Lake Harriman and the distant Marston and Patrick lakes and imagined what the land once looked like. According to one early Jefferson County pioneer: The land had never been plowed and was covered with a fine short growth known as buffalo grass. . . also many prickly pear cactus. There were no pheasants, but native birds were much more plentiful—quail, mockingbirds, orioles, bobolinks, lark canaries, humming birds and others. Blackbirds flew in flocks of thousands and would settle in cottonwood trees and all sing at the same time.” (Jefferson County Historical Commission, 1985.) Past the busy highway, I entered Bear Creek Lake Park and onto a dirt trail, also popular with dog walkers, mountain bikers and runners. At this spot, surrounded by fields, I’ve seen kestrels, red-tailed hawks, bald eagles, prairie and peregrine falcons circle on the thermals and cruise on the air currents; hover and hunt over the grass covered hills. As meadowlarks sang loudly, I climbed the dirt road on Mount Carbon, passing numerous yucca plants and a single, stunted ponderosa pine tree perched on top of a sandstone outcrop. The tree, for the longest time has had a big, twiggy, magpie nest jammed into its topmost branches. The mountain was formed during the Pleistocene or ice ages when nearby Rocky Mountain glaciers washed down alluvial gravels and sands into several layers. As time passed, Verdos gravels and clays about 640,000 years old remained on the mountain top as numerous floods flowed through the millennia and carved out around the mountain leaving much of what we find today, more of a flat topped mesa than a mountain. Rolling through geologic time, I hung a left onto a single track trail, dodging rocks and boulders on my way down the mountain. I passed more sandstone outcrops and numerous black-tailed prairie dog colonies with burrows they dig near prickly pear cactus and orange paintbrush flowers, through the shales, sandstones, and siltstones of the Arapahoe and Denver formations 63 to 66 million years old.

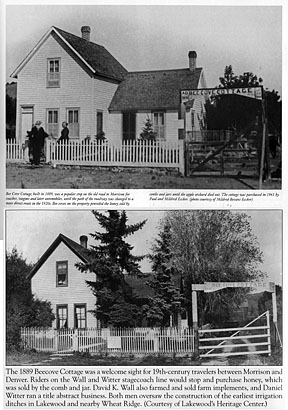

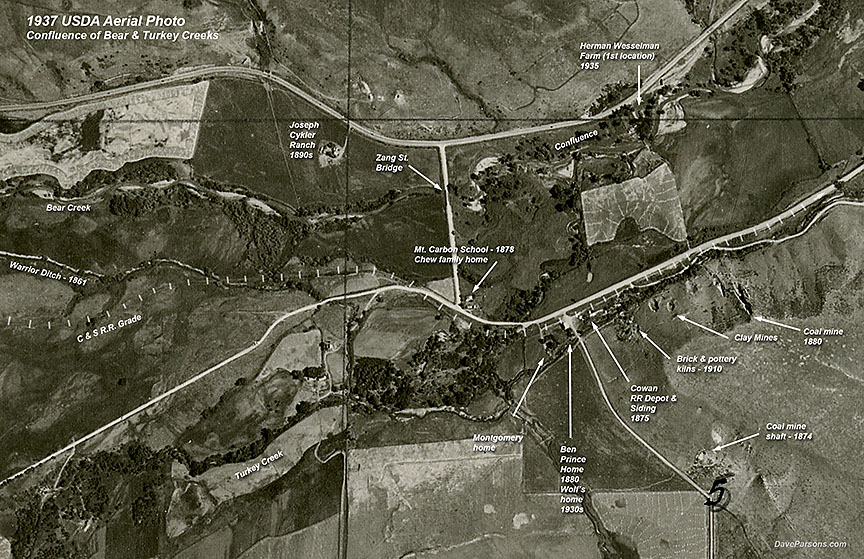

Always keeping an eye out for rattlesnakes, I spotted a healthy five foot long bull snake slithering along side of the dirt path near prairie dog mounds as a pair of black and white lark buntings flew to pointy yucca lookouts. Stopping in a cloud of dust for a moment, I watched the hunting snake with his flicking tongue test the air, creep a few feet closer to a prairie dog, pass a spiny yucca and effortlessly slide down a prairie dog burrow and completely disappear. In the past, I’ve bunny-hopped the bike over prairie rattlesnakes sunning themselves while stretched out across the trail. While running, I regularly bump into rattlesnakes on the paths at the nearby Mt. Falcon to the west. Just last summer while running, I performed a high jump to avoid an obscured, sunning rattler shaking his tail in the middle of the overgrown, grassy Red Rocks trail. Thankfully, I heard his rattle first and jumped right over him without being bit! Continuing down the hill, dark streaks of soil dusted with coal marks an area where a nearby coal mine shaft once looked out toward the mountains, now covered over, the ground is dotted with broken glass shards and rusty tin cans once used for target practice. Every spring, tiny newborn, desert cottontails use the shelter of prairie dog holes along with the adults. Crazy rabbits, seemingly drawn to run in front of me whether running or biking, zig-zag down the trail finally swerving into a dusty burrow. Staying close to their homes, a half dozen baby prairie dogs flushed down their burrow hole as I rolled past. Families of magpies hunting insects hopped around the town squawking at anything that moved. Coasting fast downhill, I quickly reached the bottom where trails converge and the land flattens out into rolling hills next to the Bear Creek Lake reservoir where in the summer, ospreys will streak into the water talons first and pull out a wiggling fish. The water now submerges the graded over remains of old cattle and dairy ranches and the small town of Cowan. Once a bustling area with mining and railroad activity, the town hosted a school, railroad station, store and a small scale brick kiln business which shipped brick into Denver well into 1914. The unincorporated town of Cowan, a focus of small scale industry was also a transportation hub in a community of dairy farms, orchards, alfalfa and pastures along Bear Creek. Articles in Morrison newspapers referred to the spot as "Cowan Curves," and "Cowan flats." In 1914, the Cowan community even owned racing horse named "Tom Todd" who won the "2:24 trot at Rocky Ford last week" with the best time of 2:21 and 1/4.Cowan was also a hotspot for early traffic accidents with drivers crashing among the many tricky curves. All times of year, during hot summer, in the snow and rain, early auto enthusiasts had to navigate the hazardous dirt roads. They could be horseshoe pocked paths, muddy ruts or flooded washes where the railroad tracks and curving lanes around Mount Carbon and over Turkey and Bear Creeks met.

Cowan was likely named after early residents in the area, an industrious Cowan family, made up of a widowed mother, Mrs. Jennie Cowan and her two sons, Claude and William. Jennie’s parents and siblings were part of an early pioneer family that traveled over the prairie in wagons and eventually set up home along Bear Creek, just east of Mount Carbon in 1870. Jennie was married in nearby Golden in 1878 to Mathew Cowan and soon had two sons. Unfortunately, her husband, a railroad engineer soon died in 1887, leaving her with two young sons. She returned to Bear Creek and her parents, Harriett and Otho H. Payne with their five acre farm to raise her boys.

Back on Mount Carbon, I scanned the prairie dog towns that sat at the base of the mountain and I looked for any predators. Numerous coyotes hunt the prairie dogs and rabbits along this stretch, with many coyotes raising large families in the nearby fields. In past years, I have watched adults raise six coyote pups through the spring and summer. While the adults were off hunting, the pups would play at their den, wrestle with each other, chase insects and play with toys, including a nice squishy flipflop, which made a good chewy toy for teething pups. Along the hillside, a long line of logs and branches extends towards the south which marks the high water line of flood waters like a dirty bathtub ring. Back in September, 2013 after days of repeated heavy rains, the reservoir filled up with a muddy goo leaving behind a valley of yellow leafed trees that looked like they had been dipped into chocolate with only the top part of the trees left untouched. Flooding has always been a part of this valley and has cost numerous lives to those living along it banks. One series of floods in the 1930’s Depression-era proved especially deadly, with 17 people washed away and drowned. According to a Rocky Mountain News article dated July 25, 1893, in Morrison, "torrents of water came rushing down the steep hillside, carrying large rocks onto the railroad track and flooding yards and gardens with mud and debris…about of two feet of sand and rocks cover what was once an acre of vegetables." The description continued: One of those tributaries, Mount Vernon Creek, bisects the town of Morrison on its descent into Bear Creek. It also flooded in August of both 1907 and 1908, effectively splitting the town in half with its massive debris moving rapids ripping between and through buildings and into Bear Creek.

Back on the trail and looking eastwards again, Mt. Carbon sits on much earlier and uplifted Upper Cretaceous, dinosaur aged rocks, 70 million years old. Fox Hills and Laramie formations contain sandstones, siltstones and sub-bituminous coal beds up to eight feet thick. These coal and clay bearing layers were vital to early Bear Creek settlers using coal for their homes and the passing steam trains and the clay for manufacturing of bricks and pottery. According to the earliest accounts, the Denver Daily Times reported on September 16, 1874, "near the western base of Mt. Carbon, coal deposits promise to supply the railroad with even more traffic." In 1881, partners Hodgson and Eaton struck a "fine vein of coal and are expected to be shipping coal to Denver in a short time." The coal companies seemed to come and go, with their names changing like the weather. Annual reports from Colorado coal mines and Jefferson County record numerous companies extracting coal well into the 1930’s.

In 1881 there was the Mount Carbon Coal, Mining and Land Improvement Company and in 1882-3, the Denver and Mount Carbon Coal Company which advertised in the Rocky Mountain News for coal "which burns longer, keeps longer without slacking and gives more heat per ton..." In 1893, four tons of coal per day were mined. In 1897, two seams of lignite coal from a drift mine dug into the side of the mountain produced 1000 tons of fuel. In 1898 the Mount Carbon Coal Company of Morrison with three employees produced 1,050 tons of coal. In 1913 "The leesers on the Cowan coal mine expect to be hoisting coal in about a week. They only have a short tunnel to drive, ten or twelve feet, to get started on the coal at 120 feet in depth. Once started it is expected that they will be able to take it out in large quantities." Finally, in 1938 the Mt. Carbon Anthracite Company with 5 employees hauled out 1,499 tons of coal. On the surface of the mountain in 1910, the Robinson Brick and Tile Company of Denver started mining clay and created the basin shaped mountain top. According to longtime Morrison resident, J. W. Van Gorden who worked in the clay mine, workers used horse drawn skimmers near the summit of the quarry to remove the topsoil and excavate the clay. Afterwards, a dirt/clay mixture was sent to Denver where the clay was separated and forced into small bricks.

Riddled with holes, Mount Carbon was a dangerous place to work and early mining was notoriously dangerous. According to one account in Golden’s Colorado Transcript paper dated December 20, 1882, an unfortunate clay miner named Joseph Albert received fatal injuries after 15 tons of clay collapsed on him while he was digging, enlarging and timbering a clay mine on Mount Carbon. "About 9 o'clock in the morning a man named Ed McDougal was shoveling away some of this clay and filling a car when he was approached by Albert, who said: "There, let me take that shovel a few minutes." He began to clear away the dirt, but had thrown but few shovels full when a huge cave in occurred. He later died of his injuries." Around 1910, the Morrison Terra Cotta Works set up a small kiln at the base of the mountain using the clay for pottery and hand-molded bricks. About the same time, "a railroad spur from the Colorado and Southern was built to provide access to the brick works (Van Gorden 1980 - Cultural Overview of the Bear Creek Area). The kiln and brick making did not last long due to a worker shortage. In 1911, a local newspaper reports The Denver Brick Clay & Coal Company purchased the Mt . Carbon coal mine and according to the Morrison Monitor of March 26, 1914 "After being shut down since September, on account of the Coal Strike, The Denver Brick, Tile and Clay Co. commenced to burn brick again last week. Mr. John Raukhol is manager of the Co. and expects to have a crew of men making brick again before long." On April 23 the same year the paper reports, "John Rankohl is shipping brick to Denver." Living across the street from the kilns, another Cowan resident, Francis Wesselman Ourada recalled a "Mr. Wolfe worked for the Denver Brick Company in Denver, but his love was working with clay and making pots and statues. He even developed a glaze that was pretty. When Mr. Wolfe had enough green ware to put into one of his two huge kilns, he would fire them up. One took 3 days to fire and one took 5 days - which meant stoking with wood 24 hours a day, never letting the heat decrease. The big oven had about 6 places that needed to be kept burning; the little one about 4. Sometimes he would catnap near the kiln. When a kiln was in process, the neighborhood would gather for a weiner roast. We would sit around and talk and laugh." (Family Memoirs - Jefferson County Digital Archives)

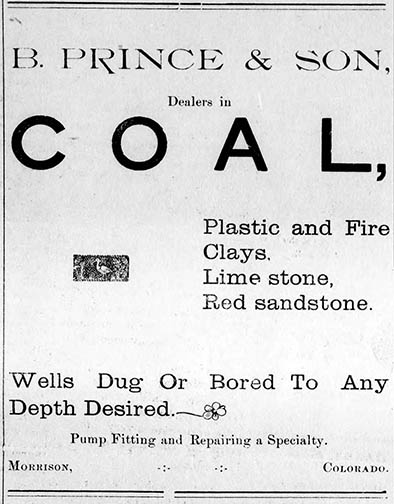

Again, Mount Carbon resident J. W. Van Gorden, who described working the earlier surface portion of the clay mine, also worked in the small brick factory and described the process of clay mining, brick manufacture and difficulties with shipping while mining a vertical vein in the side of Mount Carbon: "The clay had to be worked from beneath the vein because it never reached the surface of the mountain. They would blast the clay from the bottom, where it would fall into cars below to be taken away and sorted. As soon as the clay was filtered from the dirt it was put together and then came in on a conveyor belt. The conveyor belt led to a large wheel with wire-cutting edges on it. The clay went through the wheel and the bricks would come out in the correct size and thickness. They then took the bricks to a small, round brick kiln in which they were baked by the heat of the coal. According to Mt, Stan Renaud, the coal came from Ben Prince’s mine. Mr. Van Gorden recalled that, "it usually took quite a long time to bake the bricks."

"After the bricks were baked they were loaded on to trucks and taken a short distance down the road to the Cowan Train Station. Here they were shipped to Denver. After a while it became too expensive to ship by railroad and they began to transport the bricks by trucks. This also became too expensive which was the main reason the brick factory went out of business." (Quote from the 1976 Bear Creek High School published "Centennial - Bicentennial Bear Valley - 1776 1876 1976 USA.") Pedaling west on the trail parallel to the lake, I soon encountered Turkey Creek, a gurgling little waterway that flows from the mountains into Bear Creek Lake. Small herds of mule deer enjoy the shady trees and thick, shrubby cover along the creek as numerous frogs croak and vocalize. I’ve regularly encountered Woodhouse toads near the small check dams filled with water and along the trails. Birds of all kinds also enjoy the lake and wetlands, the area being another birding hotspot. In the spring, a small stretch of wild plums bloom along the creek, filling the air with a wonderful floral scent.

An old, well worn, Ute trail once ran by Turkey Creek, north towards Green Mountain onwards to Sloan Lake and eventually Denver. Early settlers would hunt arrowheads along the deep rut when they walked the "Indian trail" into Denver. In the past, most of the Bear Creek valley was covered in agricultural fields, cattle ranches and dairy farms. Check dams and small ponds were formed by numerous gravel mines which pulled tons of material out along the steam beds of both Turkey and Bear Creeks well into the 1970’s. Also, much of the area was graded during the construction of the reservoir dam into the late 1970’s. Considering how industrial the Mount Carbon and Bear Creek valley was, Mother Nature has done a wonderful job in reclaiming much of the area. Great horned owls, red-tailed hawks, flickers, blackbirds, ducks, geese and all sort of birds nest throughout the park. Described as a 'transition zone,' the area contains a wide range of plants and animals from both the mountains and plains.

Looking towards the lake now with cormorants stretching out their wings, I pictured the long gone District 5 school, now under water with kids in scuba gear sitting at their desks, bubbles rising to the surface as a student raises his had asking a question. On April 19, 1893, The Colorado Transcript reported: “Hon. I. A. Van Gorden has a good farm of a quarter section half a mile south of Mt. Carbon and four miles southeast of Morrison. It is mostly in alfalfa and small grains and is being improved with an orchard and small fruits. Miss Mae Abbot, a Golden girl, is teaching in District No. 5. The school house is near Mt. Carbon, and the teacher finds an agreeable home with the family of Hon. I. A. Van Gorden, half a mile distant. There are eighteen pupils and the closing exercises will occur May 26th. This is the third term for Miss Abbot in this district.” Standing near the railroad tracks by the Cowan Station, the one-room Mount Carbon school house, built in 1878 is where grades 1 through 8 were taught. It operated over forty years before closing its doors for the final time in the 1920’s when Bear Creek schools consolidated.

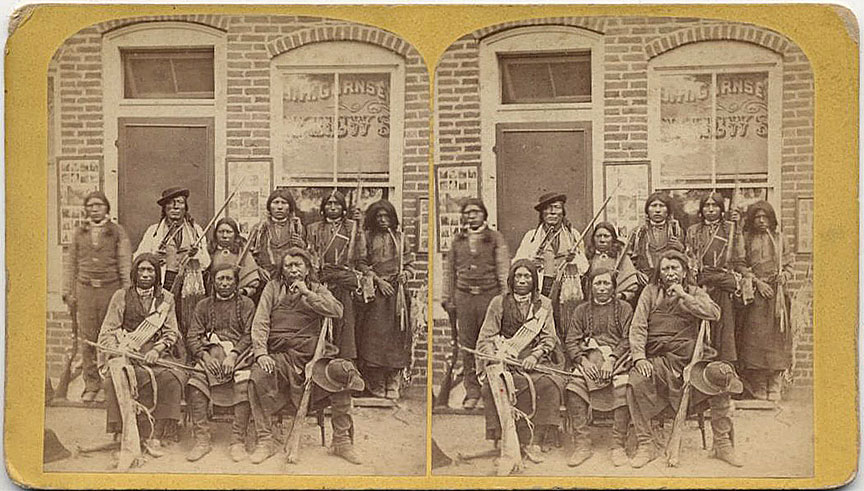

Paddle boarders and kayakers now float over where the school and the small town of Cowan once stood. Osprey enjoy hunting in this area. They will sit in the tall trees near the lake and will devour an entire fish. Making my way past a parking lot, I crossed the invisible 1870’s railroad tracks of the Morrison Branch of the Colorado and Southern railway as it headed eastwards under the lake. Chugging down hill again, I soon encountered the shady Bear Creek, with a low beaver dam crossing it’s width. Cottonwoods, poplars and willows provided welcome shade as I listened to the yellow warblers and goldfinches, numerous wrens and scrappy magpies. As a wood duck pair paddled around, water poured over a low point in the wooden dam and splashed into a pool of water in the expanding wetlands. Industrious beavers have made a massive comeback since the fur trapping days. The trail weaved along next to the river and converged with a popular equestrian trail. Horse and riders regularly cross at this spot at the river. Horses will drop their heads to take a drink and eventually splash across the creek, their hooves knocking on the river cobbles as they cross. The scene makes me think of the Native Americans that once called this area home. Similarly, Dr. Edwin James of the Major Stephen Long Expedition in 1819 reported that the Bear Creek valley, then known as Grand Camp creek, was a popular rendezvous site for local tribes and fur trappers. He detailed an encounter along the creek in 1815 with numerous tribes and trappers including, A. P. Couteau and Julius De Moon as they performed a bit of "horse trading." Dr. James recalled traveling south after crossing Clear Creek, then known as Cannon Ball Creek: "A few miles further, on the same side, is Grand Camp creek, heading also in the mountains. About four years previous to the time of our visit, there had been a large encampment of Indians and hunters on this creek. On that occasion, three nations of Indians, namely, the Kiawas, Arrapahoes, and Kaskaias or Bad-hearts, had been assembled together, with forty-five French hunters in the employ of Mr. Choteau and Mr. Demun of St. Louis. They had assembled for the purpose of holding a trading council with a band of Shiennes. These last had been recently supplied with goods by the British traders on the Missouri, and had come to exchange them with the former for horses. The Kiawas, Arrapahoes, &c. who wander in the fertile plains of the Arkansa and Red river, have always great numbers of horses, which they rear with much less difficulty than the Shiennes, whose country is cold and barren." Hopping back on the bike, I imagine throwing a leg over a mustang pony as the Cheyenne traded their British goods for Kiowa and Arapahoe horses while French trappers and "Kaskaias" or Kiowa Apache made their own trades. What a wild party that must have been - different languages drifting through the air as indigenous families prepared hides or gathered berries along the river as campfire smoke drifted around buffalo hide lodges with cooking, bargaining, haggling and noisy gambling with horse races in the open meadows! Following Bear Creek from its junction with the South Platte River, the Morrison Branch of the Denver South Park and Pacific Railroad made a relatively straight beeline to the west and the small town of Morrison. Constructed in 1874, the steel rails would roll quarried stone, lime, coal as well as timber and even Red Rocks tourist trains out of Bear Creek canyon towards the bustling city of Denver. Railroad ownership changed hands and changed names. In the 1890’s, the railroad became the Morrison Branch of the Colorado and Southern Railway. Putting the bike down, I followed the remains of the raised railroad bed the width of a single vehicle lane a foot or so higher than the surrounding fields. Chirping noisily, a family of black capped chickadees hopped around a lone tree next to the grade. Walking through the previous years remains of dry, brittle grass, it crunched under my boots. After walking a hundred yards, I found sitting top of the railroad grade, half buried, a rusty rail joint from when the tracks were removed in the late 1930's. The metal L bracket had four bolt holes across the top of its 18 inch length, two holes which bolted each length of rail together. Near the rail joint, still embedded into an old rotted wooden tie, a pair of metal spikes remained in-situ, most likely since its construction in 1874. Spikes were giant metal nails pounded into the wooden tie designed to hold down the long steel rails the wheels of a steam train rolled on during the days of the Wild West.

Turning around, I followed the grade back to my bike, looking at the remaining boulders of sandstone and limestone that had rolled off the train cars while listening to a chugging steam engine and whistle in my head. Just to the west, the pair of Soda Lakes stand next to the busy highway with their varied blue coloration. They were quarried in the late 1800's for baking soda and salt. A curious stone monument placed there by the Territorial Daughters of Colorado stands near the lake shore stating it was "on the site where pioneer settlers obtained soda for household uses during Indian raids 1864 - 69 AD." The dates coincide with the years early commerce was disrupted when many tribes including the Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Kiowa and Lakota Souix attacked settlers along the numerous wagon roads into Denver in an attempt to push out the white invaders who brought diseases and decimated their main food source, the once massive bison herds. Also, the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 where mostly women and children were killed incited many tribal members to take up arms.

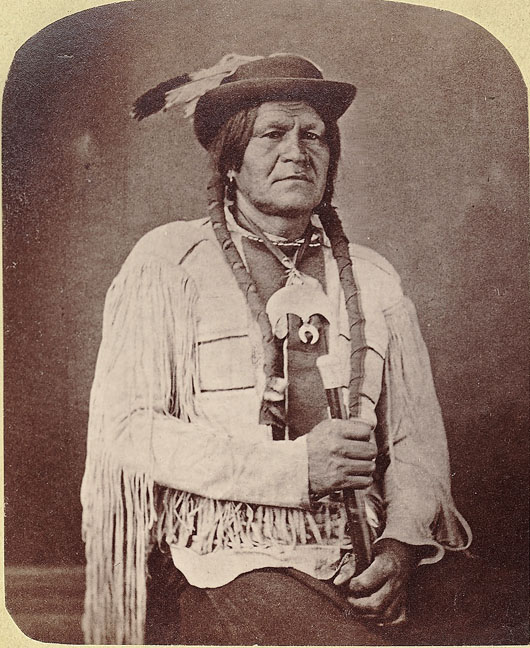

Always "friendly and welcoming" to the early white settlers, Colorow, chief of the northern Utes, was often the first to introduce himself to new residents. Rooney family stories passed down tell of Colorow helping himself to Emeline Rooney’s fine biscuits and roast beef when visiting. His clan also enjoyed mud baths in the clay and mineral springs, now on the Rooney’s Iron Spring Ranch. Other encounters involved settlers bribing Ute braves with large meals with biscuits to go away, and declining offers of trading their young family members into the Tribe. Just a few miles to the north stands the Chief Colorow Council Tree where the Rooney’s honor the long-standing peace between their family and the Utes. Also known as Inspiration Tree, the ponderosa pine, over 500 years old is where, according to Rooney family legends, the original settler, Alexander Rooney smoked the peace pipe with Chief Colorow under the tree. For centuries, the Ute passed through the Bear Creek area annually to hunt bison on the eastern plains and camped on many of the lands occupied by settlers.

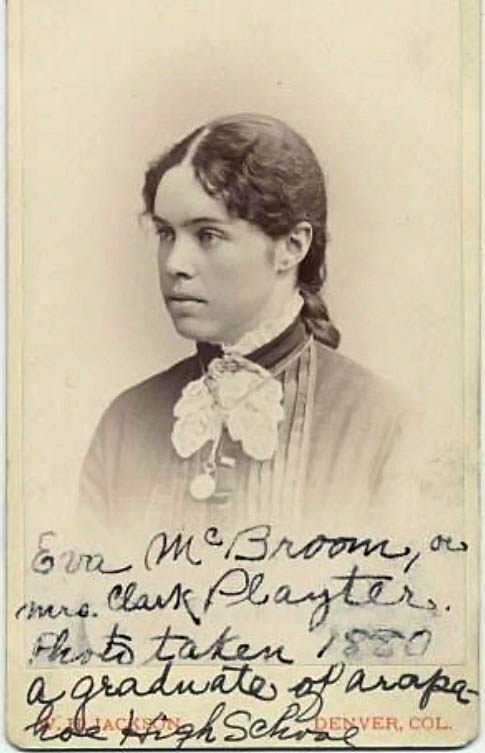

The McBroom families lived on the south side of Bear Creek just west of the South Platte River also swapped Ute buffalo hides for sugar, flour and ammunition and dined occasionally with Chief Colorow, who never missed an opportunity for a meal while traveling. According to Eva Josephine McBroom, daughter to Issac McBroom "The Utes were generally friendly and came often to trade buffalo robes for sugar, tobacco and the things we had, and just north of our place and west of Federal was a favorite camping ground for them." Issac, who set up bee hives and delivered the first native honeycomb to Denver markets also had to give up a bit of honey to Chief Colorow. Eva describes the Ute Chief: "Colorow was frequently insulting and when he found the men folks away would demand "bees kit" and "sug" from the women of the ranch homes."

Many tribes camped the area for the mineral springs and lush grasses in Bear Creek valley to feed their horses. Tipi rings, stone circles that once weighted down the edges of Native lodges and Arapahoe burials once dotted the area and are now all under homes and highways. Numerous archaeological excavations in the area have exposed thousands of years of Native occupation. Today, the Soda Lakes area hosts water skiers, paddle boarders and beach goers which flock to the sandy shores in Bear Creek Lake Park. Descending back to the river, I crossed near another parking lot that was once submerged by water during the heavy rains in September of 2013. Waters of a different sort once passed through this area when Morrison was beach front property along the Western Interior Seaway where ocean waters once sloshed 92 million years ago. Half mile west along the hogback, plant and meat eating dinosaurs left footprints that still remain today pressed into the mud of tidal flats. Like giant big bird footprints, three toed tracks, small and large crisscross each other on light colored sedimentary rock climbing the steep, uplifted hillside. In different layers close by, ripple marks are permanently frozen in sandstone along with a variety of fossils including dinosaur bones. In 1877, Colorado School of Mines geology teacher, Arthur Lakes, white taking measurements with a colleague on one of the hogbacks, found what would eventually become Colorado’s state fossil, a Stegosaurus with its vertebrae and ridge back spines six to eight inches long as well as Apatosaurus and Diplodocus fossils. It was the first discovery of three, 150 million year old dinosaurs and the first place where dinosaur bones were discovered in the American West. The discovery intensified the mad rush for dinosaur bones where fossil hunters looked to score skeletons for growing museum and university collections. The infamous 'bone wars' between Edwin C. Cope and Othniel C. Marsh even played out on the Morrison location where Marsh hoped to keep Lake's reported site secret, but, locals easily found the "secluded" site and regularly visited, even sat on the bones and helped with the digging. Today, thousands of visitors explore Dinosaur Ridge, now a National Natural Landmark. Rolling downhill, I crossed the bridge over the creek and followed the flow of the water to the east, now in the shade of cottonwood trees. Enjoying the lush green canopy, I coasted past fuchsia colored wild pea blooms or American vetch mixed in with tall grasses and leafy chokecherry shrubs. Pedaling along side the river, I passed under a great horned owl nest with two fuzzy and fast growing chicks. Taking a trail that veers to the north, I climbed through grass covered hills with fiery orange paintbrush and spiny yuccas. Always keeping an eye out for rattlesnakes, I gained the hill top and overlooked the entire valley with Mount Morrison in the west, the lake underneath Mount Carbon in the south. With no runners, hikers or other bikers below, I took a drink of water and pointed the bike downhill. Hanging on for dear life, I tightly gripped the handlebars and caught a bit of air, lifting off one of the many small rises on the path. Braking hard on a turn, I fought to stay upright while leaning into the turn. Running out my speed on the bottom of the hill, I approached the base of the dam and once again started climbing.

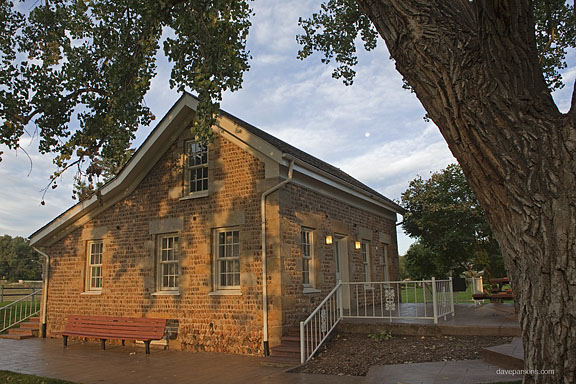

The Bear Creek Dam, started officially in 1968 was completed in 1976 and designed to stop flooding downstream for the Denver Metro area. Yet, flooding still occurs above the dam, as heavy downpours regularly fill Bear Creek Canyon and its feeder waterways with raging, muddy, waters as it did in 2013. Further to the east, some historic landmarks had been saved. The Stone House, rescued from demolition in 1974, was built in 1859 by Joseph Hodgson with hand picked round river cobbles from the creek and 18-inch thick, defensive walls with windows and doors framed with sandstone quarried in nearby Morrison. The house, added to the National Register of Historic Places, still sits on its foundation near Bear Creek. The Streer-Peterson House, also built along Bear Creek in the 1880’s belonged to settlers that were miners turned farmers and even to a family who operated a very successful moonshine operation. The early structure was named to the National Register of Historic Places and saved from being a golf course parking lot by relocating it to the Heritage Lakewood Belmar Park where it has been restored for educational purposes.

Rolling along the base of the dam I passed by the town of Cowan again where harassing magpies were nipping at the tail feathers of a red-tailed hawk perched in a poplar above the lake. Just below him, a small railroad rail, most likely used for the coal and clay mines, stuck out of the hillside where the reservoir water has eroded the soil. Also graded over and eroding out of the hillside were the trash remains from the 1920s and later. Broken glass bottles with raised lettering had labels of Mason, Pasteurized Citrate of Magnesia, Lavoris, Texglo and Royal Family (Artifacts now reside at the Bear Creek Lake Visitors Center, some on display). Clear glass was mixed with bricks, small automotive parts, green depression glass, light sockets, spark plugs and rusted metal blobs. Once again, I pictured a steam engine chugging by, slowing for the train station while miners pulled coal and clay out of the hillside and kids ran to the store after classes from the small school house. I wondered who last used the glass bottles or was replacing the spark plugs in their old car.

On a later, evening visit to Bear Creek, I drove past the 1859 Stone House and walked along the Bear Creek Trail, overlooking a massive beaver lodge as the sun set behind the silhouetted Rocky Mountains. Silently, a great horned owl glided over the river and landed gently on a branch overlooking the widened waters of the dammed river. Slowly rotating his head like a surveillance camera, he looked through the thick forest and then smoothly swiveled his head 180 degrees to look at the waters edge, searching for prey. As muskrats and beavers paddled in the river below munching on juicy twigs, American dippers dove into the cold waters and performed their dipping dances on rocky perches. With growing darkness, tiny brown bats emerged with their high pitch chirping. Energetically echolocating, their leathery like wings flapped at furious pace as the tiny insect eaters swerved wildly in their aerial acrobatics devouring moths and mosquitos. The sky, now the darkest blue began to fill with stars as silhouetted ducks and geese flew over in small flocks landing with splashes in the darkened river. The night crew of unseen creatures emerged as cool breezes flowed down the river. Sitting along the flooded stream bank near the water, I enjoyed the brightening moon and listened to the sounds of the night and the river tumbling down Bear Creek valley as it has for centuries.

|

All contents copyright ©Dave Parsons

DP Home | Feature | Gallery | About