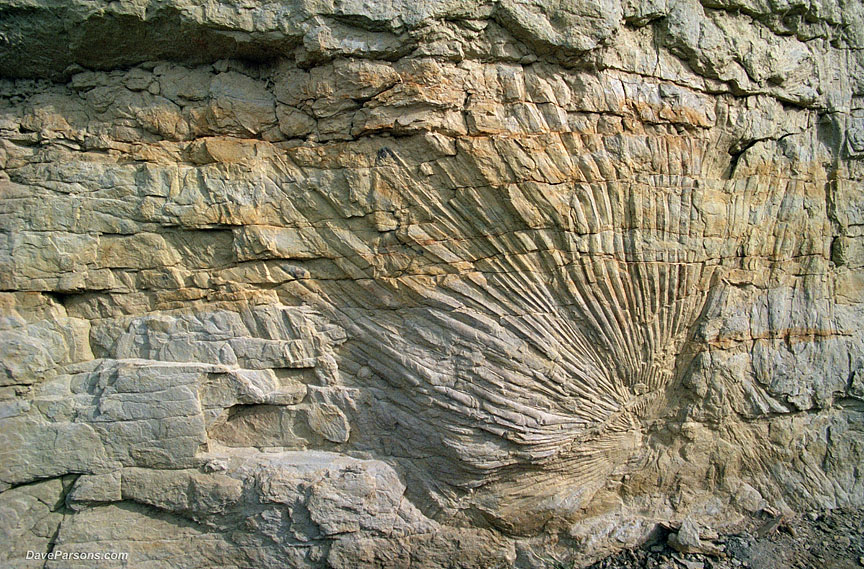

Exposed by clay mining in early 1900s and frozen in time, a spectacular 68 million year old tropical palm frond fossil in Golden Colorado's Triceratops Trail exhibits the diversity of life in the Late Cretaceous Laramie formation which also produced massive amounts of coal mined along the Front Range. Photo taken on November 9, 2002 by David Parsons |

Littleton's Trio of Troublesome Coal Mines

by David Parsons - November 18, 2025

Squishing through hot and humid coastal swamps while brushing past palm trees and lush tropical plants, Tyrannosaurus rex stalked his prey. As mosquitos buzzed around his head, the toothy predator eyed his spiked food, the tri-horned Triceratops. About 68 million years ago, this daily event occurred literally in todays backyards near Colorado's Front Range hogback.

A unique area, layers of ancient sediments of decaying plants and animals once living in a diverse ecosystem along the Cretaceous beachfront property of North America's Western Interior Seaway accumulated over millions of years. There was such an abundance of plant life in the Colorado area during this time that fully one-fourth of the area of the state is underlain with coal seams (DMNS - Fossils). Likewise, deposits throughout the Late Cretaceous and later ages eventually rendered into today's dynamic dinosaur and plant fossils, limestone, sandstones, mudstones, gravels, clays and coal that sustained decades of Colorado's mining including a trio of troublesome coal mines near Littleton.

These exceptional depositional layers, bent and warped through mountain

building and the birth of the Rocky Mountains eventually eroded revealing useful resource extraction points along the hogback and on the eastern plains. As Denver and the surrounding cities grew, resources like coal for powering steam trains, heating and industry, lime for cement and clay for sewer pipes, fire bricks and building became more in demand. Mines and lime kilns popped up all along the hogback co-locating with coal and clay bearing layers exposed in the rock.

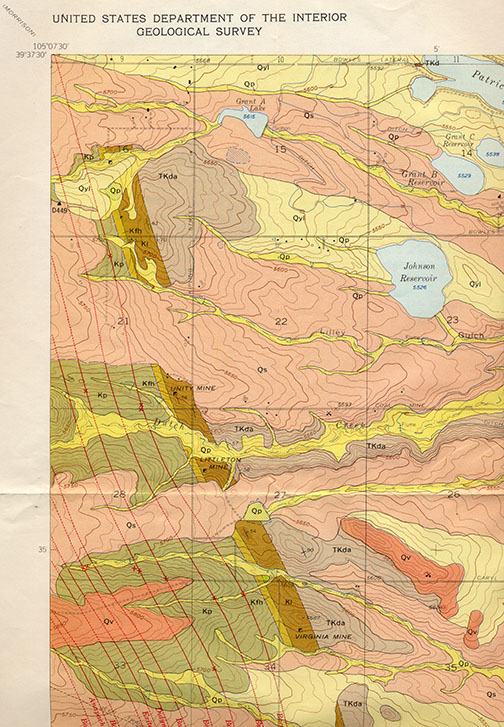

Ancient deposits lie underneath more recent erosional flows along Colorado's Front Range revealing a multitude of useful products including clay and coal. Three mines located in the coal producing Laramie Formation sit along South Kipling at Coal Mine Avenue in Littleton, Colorado. Map from Parsons Collection

(Kl - Laramie formation, Kfh - Fox Hills sandstone, Kp - Pierre shale, Qs - Slocum Alluvium, Qv - Verdos alluvium, TKda - Dawson arkose, Qp - Piney Creek alluvium, Qyl - Younger leoss) - Map from 1957 "Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado." - Parsons Collection |

Today, front range limestone and clay mining have exposed remains of those ancient landscapes with large angled sections of rippled sandstone, layers of swampy fossil remains and even dinosaur bones and tracks. Golden's "Triceratops Trail" and Morrison's "Dinosaur Ridge" are amazing examples of exposed geology and fossils.

Yet, other aspects of the areas geology are more hazardous for the 21st century and are hidden beneath much of the areas development. Many of the nearby roads suffer from expansive soils of the Pierre Shale, an ancient marine deposit which causes the roads to rise and fall with, at times, surprising abruptness. Similar geology effects many of the neighborhood foundations and cement driveways built in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s with alarming cracks as they slide around on poorly mixed soil filled with bentonite and clay also from the Pierre shale and Piney Creek alluvium.

Despite todays housing hazards, the front range geology has mostly benefited the local population during Colorado's early years. Coal mining warmed entire towns, fueled industry and jobs. Built along the coal bearing Laramie formation, many of the first mines were established in the late 1800s like the Lehigh Coal mine near Sedalia or the Mount Carbon and Satanic Coal mine in Morrison which opened in 1872, when steam trains were headed to the gold mines in the Rockies.

However, east of the hogback on the plains near Littleton, a trio of later coal mines in the Foothills Coal Field in Jefferson County established in the 1920s and 1930s have a mixed record. They were called the Christensen Mine (later the Littleton Valley Mine or just Littleton Mine), the Unity Mine (later called the Economy Mine) and the Virginia Mine. These three mines sat just off South Kipling Avenue and near the appropriately named Coal Mine Avenue.

Today, the mine sites are almost invisible, mainly flattened out parcels of dirt with a few sidewalks running through them. No mine structures remain and mapped mine and air shafts are filled and capped. However, despite the threat of subsidence and sinkholes, home builders dangerously constructed homes directly over one mine (Virginia coal mine) and on the edge of the other sites (Unity and Christensen), coming very close to building on hidden, underground and unknown mine shafts. Areas surrounding the mines are large housing developments with a maze of roads.

Most material evidence of Littleton's coal mines

have long been sold and carted off in foreclosures or "Sheriff sales." The mine shafts themselves have been mostly filled in, initially with mining debris and later re-filled and capped with cement. The small surrounding areas have become tiny open spaces, havens for jumping bikes, prairie dogs and dog walkers, and interesting spots to explore - just be aware!

The Unity Mine which later became the Economy Mine stood just south of Coal Mine Ave. just west of Kipling Avenue and across the street from the Christensen Mine. More fire brick and another shaft filled with water and debris has a railroad rail sticking out near a cement slab. The photos were taken in March of 1998. Today, the area is completely graded over and sits near a housing development. David Parsons photos. |

Not all the history was removed or buried, some of the early history still survives. In the 1990's, stacks of fire bricks remained at the site of the Unity/Economy and Christensen/Littleton Mines which ran from the 1920s into the early 1940s. The Laramie Formation, not only produced fossils and coal, but was also a major source of brick clay. Fire brick foundations at the Unity mine indicate there was a possible kiln near the mouth of the mine perhaps using the coal to manufacture more bricks or fire clay products.

Or, more likely, the bricks, with their excellent insulating properties, were used to line the on site boilers and furnaces. Boilers and furnaces were used to generate steam and heat, which were essential for powering equipment and providing warmth for workers in the mine shafts. They also helped in the mining process with drilling and transporting materials.

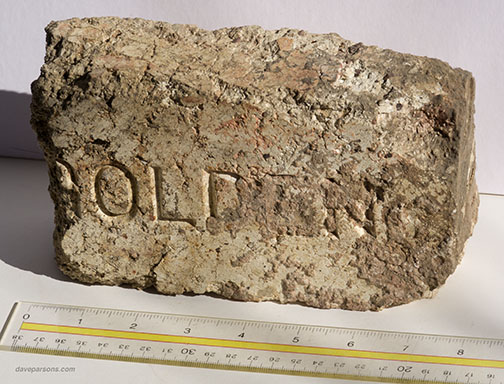

Some of the same type of bricks are found throughout the Christensen mine, including locally manufactured "Denver Fire Clay Company" and "GOLDEN" fire bricks (PDF). Also, red bricks for building homes and structures dotted the Christensen mine site, likely from the two cottages or boarding house also on the site. Individual railroad rails that once shouldered heavily laden coal carts stuck vertically out from submerged mine shafts at both sites.

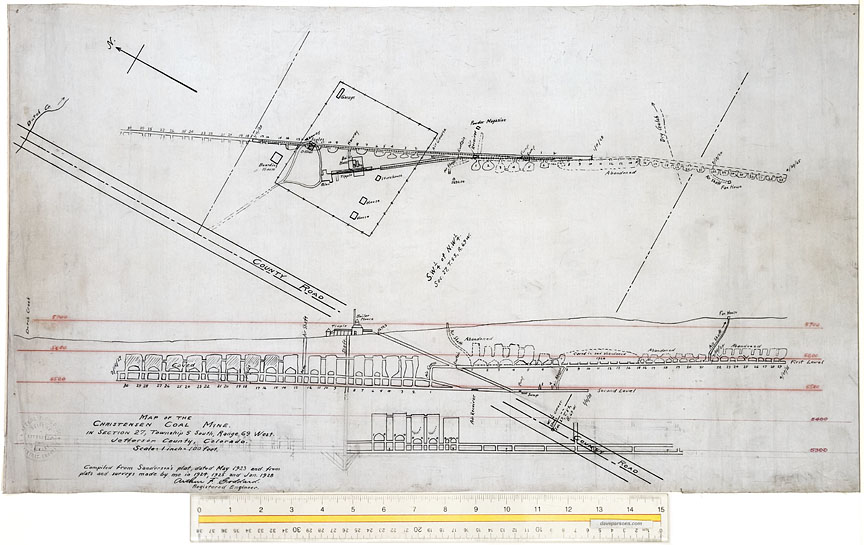

Original hand drawn 1923 technical schematic of the Christensen Coal Mine, by Registered Engineer Arthur F. Goddard and updated in 1924, 1925 and 1928. Scale - 1 inch equals 100 feet. 1979 and 1988 sinkholes occurred near the first level of 1924 and 1925 diggings in sections south the air vent or on the far right of the illustration. In later years, the artist sketched in mine extension in the lower left which was updated in another 1930 mine drawing from Thomas J. Knill. From Parsons Collection (While writing this story, the two mine drawings came up on eBay, November, 2025) |

Hand drawn technical schematics of the Christensen or Littleton mine indicates the "room and pillar" method of mining was used, borrowed from 1860s English miners.

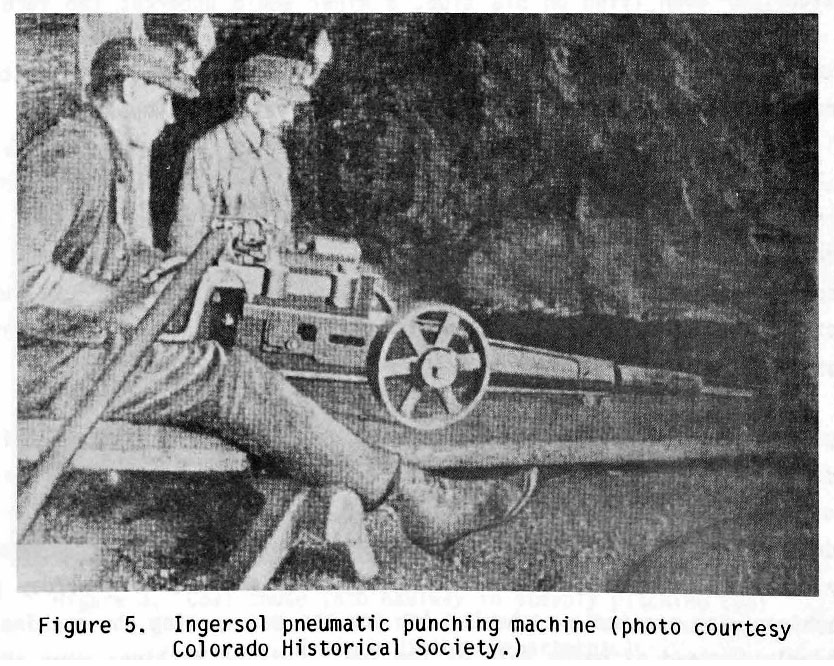

The 1934 auction sales list shows nine pneumatic or compressed air Ingersol punching machines were used at the Christensen Mine. I. R. punchers were a "three-pronged pick which cut an angled trench below the working face." From p. 30 - "Proceedings of the 1985 Conference on Coal Mine Subsidence in the Rocky Mountain Region" - Colorado Geological Survey. |

"The entrance to a room and pillar mine could be vertical, called

a "shaft", or horizontal or sloping, generally referred to as a "slope" (downward

from entrance) or "pitch" (upward from entrance).

At the bottom of the entrance shaft or slope would be the main passageway into the

coal seam, generally called a main "entry", "haulageway", or "motor road" (when

electric motors used for haul age of the coal). This entry was nearly always a

"double entry", two parallel tunnels oriented such that fresh air was blown in one

tunnel, circulated through the mine for ventilation, and exhausted through the

second tunnel. The two halves of this double entry were separated by a chain

pillar about 50 feet wide."

"The length of these rooms varied, depending on the location of the room in the mine and the period during which it was mined. When adjacent rooms were mined to their final length, the pillars between the rooms were mined, or "pulled" as the miners retreated from the room." ("History and Evolution of Mining and Mining Methods" - Stephen S. Hart)

The 1934 auction sales list indicates Ingersol Rand (I.R.) punching machines were used in the Christensen Mine. The pneumatic or compressed air devices, introduced around 1880 increased production 50 percent from the old "pick mining days." It was a "three-pronged pick which cut an angled trench below the working face."

There was also the typical mine infrastructure supporting the site including a garage, powder magazine, storehouse, fan house, office, boiler house, storage bins, scales, coal tipple with railroad tracks leading from the mine shaft, and the boarding house and two houses. On January 6, 1922, the Littleton Independent newspaper reported that:

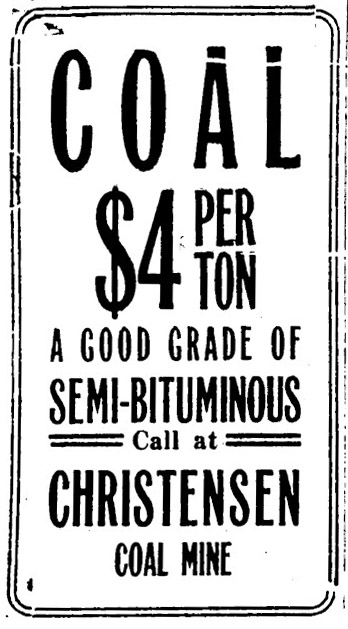

Advertisement from the Littleton Independent newspaper, 1922 |

"A boiler and steam hoist have been moved to the Christensen coal mine west of Littleton and Mr. Christensen is making preparations to take out a great quantity of coal. Eleven feet of bright shiny coal of an exceptional quality for this district has been opened up at a depth of about 80 feet. There is plenty of water and the coal is getting better every foot as the shaft is sunk. There is little doubt now that Mr. Christensen has opened one of the best coal fields in the state and there will be much coal taken out between Littleton and the foot-hills."

That year, over 2,000 tons of coal was mined, with some years in the 1930s producing over 18,000 tons of coal being removed in one year. Advertisements promote a "good grade" of coal ready for pick-up at the mine or delivery through middle-men. The mine schematic shows a driveway circle in front of large coal bins at the base of the coal tipple which would have held coal of various qualities. Scales also stood near the office for weighing a truck load.

According to an interview with Mr. Christensen, the former operator, "the mine contained 4 coal beds; the lowest bed pinched to 4 feet, swelled to 27 feet and averaged about 6 feet in thickness. The Thickness of the higher 3 beds were respectively 2 feet, 18 inches and a very light show. The coal was mined from a shaft that was 490 feet deep. The bed dipped nearly vertical for 700 feet and then flattened out. The best coal, found at depth was hard and had to be blasted, however blasting reduced the coal to slack and the price of slack coal was too low to allow profitable operation of the mine. After an accident in which two men were asphyxiated, the mine was closed; it became filled with water and has not been reopened." (p. 41 Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado)

From Littleton Independent, 1922 |

Surface artifacts on the site affirms there was more than just mining at the site as broken dishes, pieces of large crock pots, delicate tea cups and flowery bowls once help feed hard working miners from the 1920s and 1930s. Some of the more identifiable shards were from a pair of blue plates with a Chinese flair of a willow tree, pagoda, small boat and other intricate designs. They were manufactured by Allertons Ltd. of England using the popular "Blue Willow" pattern, a ceramic transferware that dates from 1929 to 1942.

During a visit in November, 2025, kids and prairie dogs had dug up 1920s - 1940s artifacts throughout the area, making trails, dirt bike jumps and burrows. The heavy steel girder was likely part of the superstructure of the mine. Glass plates, china and huge crock shards littered the area. Pieces of the blue plate were from Allertons Ltd. of England. The "Blue Willow" pattern, a ceramic transferware dates from 1929 to 1942. The straight edge, rectangular, but small shovel could have been used to clean the clinkers or slag out from under the boiler. Various bricks also dotted the area including red construction bricks, Golden and Denver Fire Clay Company bricks. David Parsons photos |

Near some of the dirt bike jumps and where the railroad rail pokes out of the ground, a three foot long, rusting steel girder with tightly spaced rivets, likely a remanent of the mine superstructure sits bent up and broken. Nearby, a broken and bent drill bit sat on the coal dusted surface. Chunks of broken cement, likely from the mine's other structures get a second life reinforcing bike tracks and jumps. An area just above the rusty beam remains closed off with a chain link fence topped with barbed wire - is the site of an old mine sinkhole.

Sitting on the coal dust covered surface, a bent and rusted drill bit remained where the main shaft of the Christensen Mine once stood. The bit, along with a compressed air drill and miner likely drilled tons of coal creating the long, underground mine tunnels. |

Back in 1988, a 17 year old teenager walking through the prairie dog filled site found a large sinkhole eight feet wide, 25 deep and 30 feet wide at the bottom. Other kids explored the site behind the homes and word got out to one of the parents who notified the Jefferson County sheriffs department who notified the federal Office of Surface Mining. This sinkhole was apparently a repeat of a 1979 incident where a 100 foot deep sinkhole developed only 100 yards away. Unsuspecting homeowners living next to the open fields that once housed the coal mines have feared for their children's safety and even for the structural integrity of their homes. Both of the collapses were filled in and capped, but the unstable subterranean events freaked out residents who sued the homemakers after the first sinkhoke for not disclosing their proxmity to abandoned coal mines. 20 of the homeowners were awarded $220,000 in damages by a jury in 1986.

Again, Looking at the hand drawn schematic of the mine, the collapses occurred near the first level of 1924 and 1925 diggings in sections on the south end of the mine near an air vent (or on the far right of the illustration).

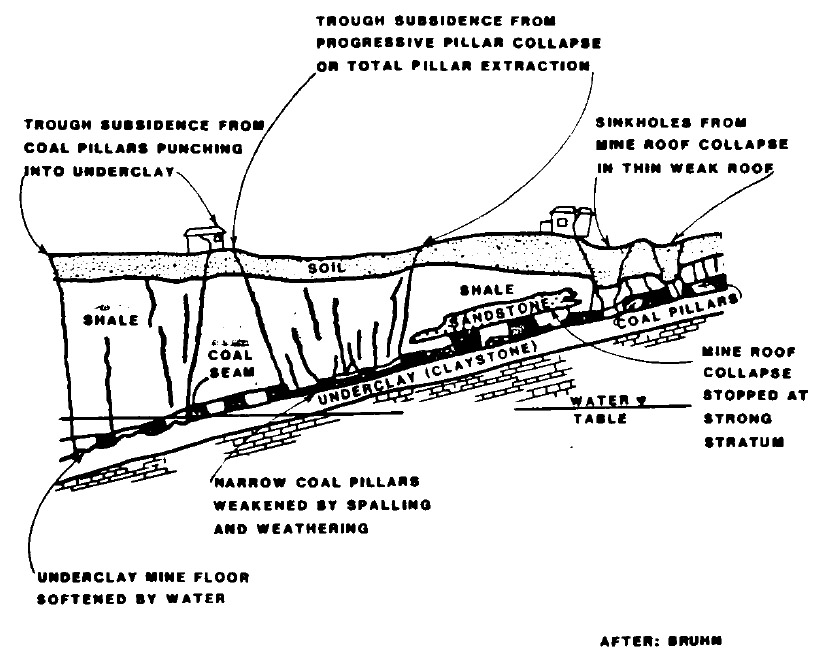

Modes of subsidence over a room-and-pillar mine. From "Proceedings of the 1985 Conference on Coal Mine Subsidence in the Rocky Mountain Region" - Colorado Geological Survey. |

Almost a decade earlier according to a Rocky Mountain News report on November 17, 1979, the Office of Surface Mining spent $138,000 to permanently cap the ventilating shaft of the Littleton (Christensen) Mine which was originally filled in 1937. Yet, several homeowners remained worried, especially the family whose child discovered an alarmingly deep abandoned mine at the nearby Virginia Mine shaft, 4 feet wide and 140 feet deep that "had caved in behind his house near Kipling Street and West Geddes Avenue ." Yet despite the danger, "The area adjacent to Stony Creek in which the shaft lies is designated to become a county park."

"Old mine shafts, common in Boulder, Jefferson and Weld counties, were capped when the area was mined out in the 1930s. However, trash and wood, which eventually deteriorates and collapses, generally was used to cover the shafts."

"The locations and likelihood

of collapse of the Virginia and Economy sites aren't known." (11-17-79 RMN)

Looking west towards the Front Range foothills and the sites for the Christensen and Unity Coal Mines with an overlaying schematic of the mine. The photo was taken on March 23, 2001 and still looks much the same today with black, subbituminous coal staining the area. |

The abandoned Christensen/Littleton coal mine was not only prone to surprising sinkholes, but while it was active, miners had to avoid numerous cave-in areas and also suffer from long term health effects from exposure to mine dust which caused debilitating black lung disease.

Many family trees have the life long coal miner from generations ago. These brave souls also worked in the trio of mines along Kipling's Laramie formation harvesting deposits of subbituminous coal, sometimes with deadly consequences.

In a L. C. McClure glass plate negative taken about 1915, miners wear no masks or protective gear as the dust flies while they dig and drill in the heart of a coal mine in Sparlin, Colorado on the Denver and Salt Lake Railroad (In between Kremmling and Granby). Photo from Denver Public Library Digital Collections |

As mining became more difficult and sections harder to access, some areas of mines were closed off and new areas opened up. Many of the old sections became too dangerous to enter and repeated collapses would have occured. Often times cost cutting management ignored safety inspections and violations in an attempt to save a few bucks and working conditions declined. In one case at the Christensen Mine, a section of coal was ignited and burned for months producing deadly mine gases.

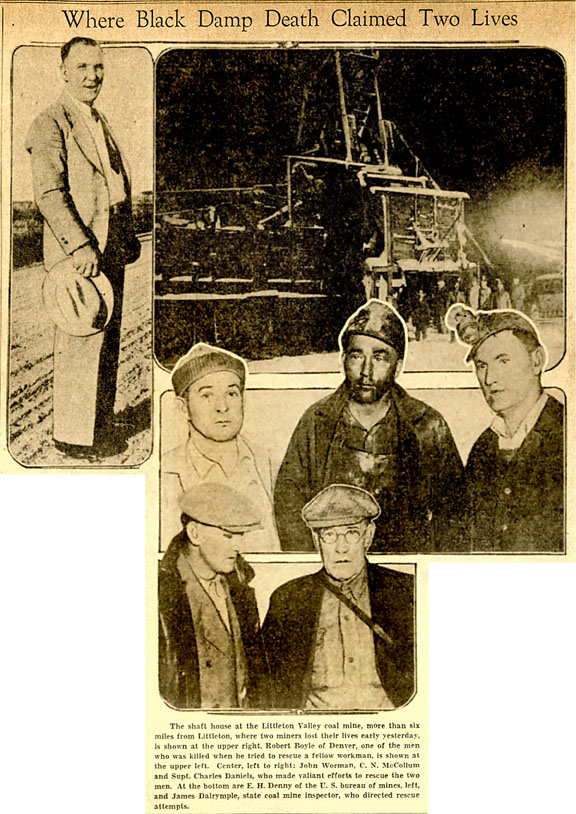

Similarly, in 1933, disaster struck the mine. According to news reports, a portion of the mine in the older section had been burning for 11 months previous and mine inspectors ordered the area to be cemented off. Unfortunately, the shaft was never sealed and resulted in a buildup of toxic gas which overwhelmed two workers and eventually led to their their deaths. Heroic efforts were made to rescue the workers but they were too late. The bodies of Martin Kranledis, 44, of Littleton and Robert Boyle, 42 of Denver were rolled out in a mining cart by Denver Fire rescue squad No. 2. The December 3, 1933 Rocky Mountain News reported the first to die was Kranledis,

"When he went down the mine shaft to oil machinery. Boyle died in an attempt to rescue his fellow workman, drove back by gas. The two men were overcome late Friday night and other miners and company officials made repeated attempts to rescue them, but were driven back by the deadly gas. Finally a Denver fire department rescue squad was called and, donning oxygen masks, then went into the dark interior of the mine and found the two bodies. Miner after miner had risked his life previously in attempts to rescue the men. The Littleton fire department also was called, but not until he Denver rescue squad arrived was anyone able to bring out the two corpses. Called negligence the inquest, held in a building near the mine, revealed that, Oct. 4, the state coal mine inspector had ordered the old workings where fire was burning to be blocked off with cement wall. The verdict of the coroner's jury blamed C. C. Daniels, S. K. Burnett and N. C. McCallum, directors of the company, for failure to carry out the safety instructions. It was declared that the directors "were negligent in not complying with the state coal mine inspector's instructions for permanent stopping of the shaft where the men met death.""

Photos of the mine and men. The report of the sad results due to negligence was from Rocky Mountain News - December 3, 1933 |

Soon after the deaths of the men on March 29, 1934, the Jefferson County Recorder listed the mine contents in a Sheriff’s sale which were to be sold off in a auction after a judgment against the Littleton Valley Coal Company. After more than a decade of producing coal the mine shut down. The list contained:

-

Just a few months after the deaths, the mine ceased production, filled with water and was was sold off in the spring of 1934. From P. 42 - Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado - Parsons Collection |

3 steam boilers

- 2 hoists

- 1 shaker and engine

- 2 coal bins

- 1 head frame equipment

- 6 pumps

- 3 air compressors

- 9 I. R. puncher machines

- 2 lack machines

- 8 jack hammers

- 5 stokers

- 1 air drill

- 34 pit cars

- 3 skips

- 3 mine cars

- 8 chutes

- 7 air receivers

- 1 rotary screw

- welding outfit

- 1-10 car garage

- 2 cottages and all tools, dies, cables, iron rails, pipe and pipe fittings, valves, tanks, machine parts, pulleys, scales, lubricators, hoists, injectors, fans, engines, harness, elevators, and mine equipment and office furniture and equipment used and located at The Littleton Valley Mine (From Jefferson County Reporter, 1934)

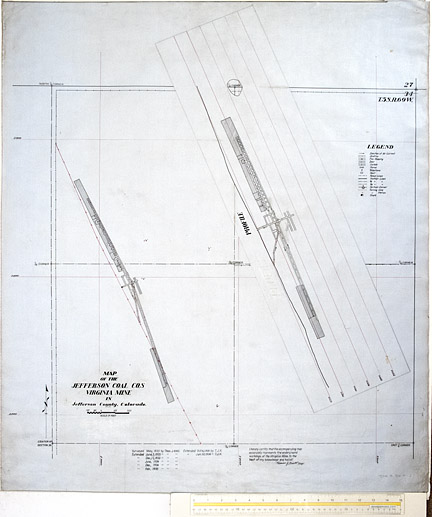

Original hand drawn 1933 technical schematic of the Virginia Coal Mine by Registered Engineer Thomas J. Knill and updated in 1934-1936. Despite being incomplete without extensions up to 1939, the drawing still gives an idea of the area of the mine. From Parsons Collection (another timely discovery found on eBay, November, 2025 while writing this story) |

After the Christensen/Littleton coal mine closed down, the nearby Virginia mine was still producing coal. And it has also caused numerous headaches for homeowners.

Located on the same Laramie Formation, the abandoned Virginia Mine that operated from 1933 to 1939 happened to be the exact spot Dallas developers decided to sell home sites at, and even locations right on top of the mine shaft!

As a result, "Thirty-four families sued Robert J. Sabinske of Dallas and his National Development Co. after county officials warned them in 1981 of the dangers of building over the old Virginia Coal Mine. Some homes built in the area were damaged when old coal tunnels began to collapse. Those who purchased property in the Fairview Heights subdivision then filed suit, complaining the land was worthless."

The suit stated the "existence of the mine has been a matter of public record since Sabinske bought the property in 1955. The commissioners approved the area for building in 1956, the lawsuit said."

"A 1977 study for the county also showed the existence of the mine, the suit says."

"

The exact location of the mine has not been determined, a county spokesman said. The only clue to its whereabouts is a map filed by the coal company while it was operating the mine. If-that map is accurate, one house is built directly over the mine tunnel." (RMN - 1-27-82)

Some of the Jeffco residents even received a letter from a Denver consulting firm describing their situation "as potentially life threatening." (November 26, 1988 - RMN)

A few years earlier on November 15, 1985 (RMN), a child sledding near the area over the mine between a shopping center and self service car wash had to be rescued after sliding into an expanding mine sink hole 10 feet wide and 14 feet deep. The hole, when originally discovered was 3 feet wide and 6 feet deep. "The hole, is bigger at the top than at the bottom, so there's an overhang," said John Rold, director of the Colorado Geological Survey. "Its impossible to get out without a ladder or rope." "... I wouldn't park my car within 20 feet of the hole." "(The abandoned mine) is certainly a public danger," and "It will happen again and again. When you create a big hole in the ground, sooner or later it will come up and get you" stated Don Donner, chief of the Federal Reclamation Project Branch of the Office of Surface Mining. The 20-foot-deep sinkhole had to be filled with 12 truckloads of dirt.

According to a Colorado Geologic Survey 1985 report (PDF) "The Virginia Mine Subsidence Hazard Investigation was undertaken in early 1982. The study showed that 44 homes were in a seven acre zone that could potentially be influenced by mine subsidence. Eleven homes were located in a relatively severe subsidence hazard area."

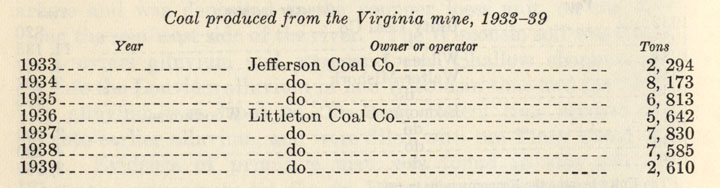

Coal from the Virginia Mine 1933 - 1939. P. 42 - Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado |

Likewise, "Some homeowners have contended that their homes were physically damaged by subsidence in the mine, and two families have moved away, said their attorney... A district court jury in March 1985 concluded that Sabinske and National Development were liable for the properties' loss in value because they sold the lots without telling buyers about the mine."

In the end, the single largest award of $145,000 went to the family whose home was "one of four located directly atop the long-abandoned Virginia Coal Mine in the Fairview Heights subdivision." In separate trials "juries awarded $220,000 to the owners of 20 vacant lots and $304,000 to the owners of four homes."

In 1981 Jefferson County officials designated a geological hazard zone in the area of the mine, meaning that no additional development could take place." (November 6, 1985 - RMN)

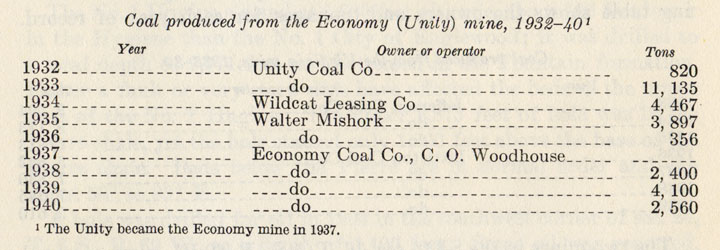

Coal from the Unity - Economy mine from 1932 to 1940. P. 42 - Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado |

The nearby Unity Mine had its own problems as it passed between different operators every other year.

In 1934, depite a huge year of production of over 11,000 tons of coal, there was another Sheriff's sale to sell off mine assets. The list gives an interesting look into what ephermeral infrastructure was used at the mine and what it took to run the coal mine. The sale included:

- 1 temporary, galvanized, corrugated iron covered building now at air shaft of Unity Mine

- 1 temporary frame structure, scales house and office at Unity Mine.

- 1 temporary powder magazine at Unity Mine, corrigated iron.

- 1 corrugated iron shed or barn at Unity Mine.

- 1 Frame water closet at Unity Mine

- 1 Galvanized, corrugated iron engine house, boiler room, including machine shop and shower room, together with any and all timbers, braces, structural iron, etc. used in the construction of thereof

- 1 Coal mine tipple, together with all coal bins for holding the various kinds of coal, covered with galvanized, corrugated iron, together with screen, structural iron, bridge braces, bolts, braces and iron used in the construction of the same, and all framework and lumber in the construction of said tipple.

- 1 screening shed with bins covered with galvanized, corrugated iron, together with all timbers, structural iron, lumber and braces in connection there with.

- 1 4x10 Air Receiver; 35 Feet 5-8" Air Hose; 80 Foot Conveyor Chain; 4 Sprocket Wheels; 4 Boxes; 700 Feet Sheet Iron in Bins; 300 Feet Angle Iron in Bins; 2 3" Flat Boxes; 1 18" Sprocket; 1 6-ft pc. 2-7/16" Shaft; 2 Take-up Boxes; 2 Bearings, 2- 7/16", 1 Screen and Shaft; 2 Bearings, 3-7/16"; 1 8 tooth Sprocket; 1 12 tooth Sprocket; 1 Piece Shafting; 2 Sets 30 lb. Frogs & Switches; 30 30-ft Splice Bars; 20 1/4" Anchor Bolts; 14 Ft. 4 1/2" 4-ply Belt; 1 Pulley 20" by 5 1/2 x 2"; 102 Ft. 1 1/2" Pipe, 219 Lb. 12-gauge iron; 2 6" Flange Unions; 1 7" Elbow; 6 Ft. 7" Pipe; 1 Hoist and wire rope together with all grease cups, lubricators and all fixtures complete and steam pipe from boiler to hoist (see photo below); 13 Pit cars; 1 Lumber car; 2 30 lb. switches; 30 Conveyor Buckets; 1 Automatic Tipple Dump; 5 Rollers, 1 Concave Roller; Adjustable stock and dies; 1 Pipe Cutter; 1 Jack Hammer; 10,540 Pounds of 30 lb. rails

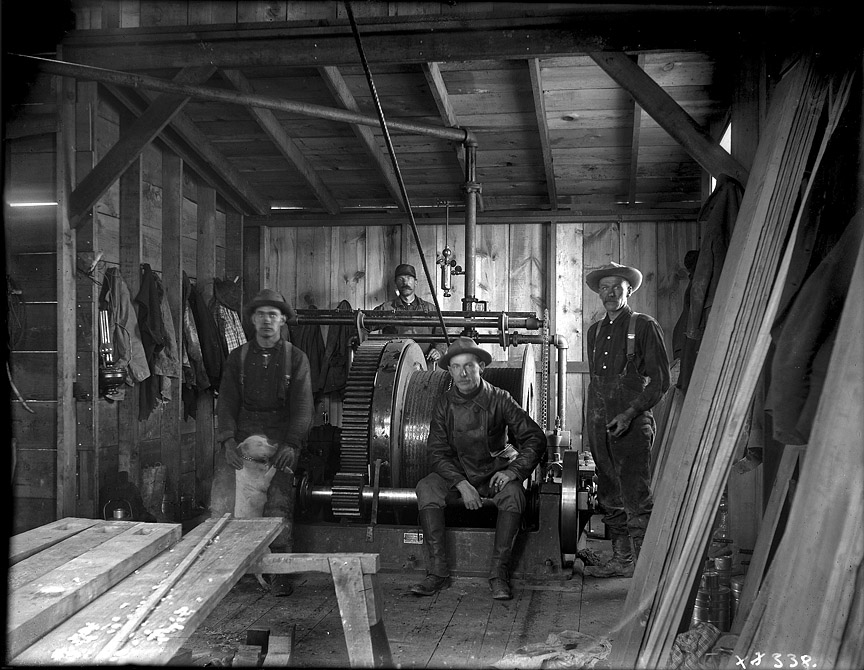

Taken by photographer Joseph Sturtevant around 1900 near Boulder, Colorado, a glass plate negative shows miners with their dog sitting around a steam driven hoist, similar to what would have been used in the numerous Jefferson County coal mines. Notice the high pressure steam pipe feeding into the hoist, powering an engine piston and then turning the drum. Similar high pressure pipes were found at the Christensen Mine. Photo from University of Colorado Digital Library |

Ore carts similar to these would have been used at the Kipling coal mines. The nearby clay mines (Parfet Clay Pits) in Golden used these 1920s era rocker dump cars. These cars were on the Colorado School of Mines property on November 11, 2001 during the opening of the Triceratops Trail. The carts were manufactured by C. S. Card Iron Works Co. of Denver Colorado. - David Parsons photo |

A couple of years later, according to the Jefferson County Republican, a fire had started in the mine in 1936. The paper recorded "A fire started by an unknown cause in the Unity mine on the property of Mrs. Ida Bailey Smith, was extinguished and the mine sealed up."

The mine reopened in 1937 under new management and continued to produce coal up to 1940 under the Economy Coal Company and was then sold off in a chattel mortgage sale on "Saturday, June 21, 1941, at 10 o'clock A. M. at said Economy mine, offer the said mining machinery, tools, and equipment for sale at public auction to satisfy the indebtedness secured by said chattel mortgages." (Jefferson County Republican - 6/19/41)

Decades later in 1985, residents near the Economy/Unity mine sued the same home builder that constucted homes near the Christensen Mine. According to a March 1, 1985 Rocky Mountain News report:

"Twenty-eight homeowners in two subdivisions southwest of Denver have filed a lawsuit against the company that built the homes, claiming they were built in a "geologic hazard zone." The lawsuit, filed this week in Golden District Court, alleges that U.S. Home Corp. was negligent when it built the homes in the Westbury and Foothill Green South subdivisions near the inactive Economy Coal Mine in Jefferson County. It is seeking compensatory and punitive damages."

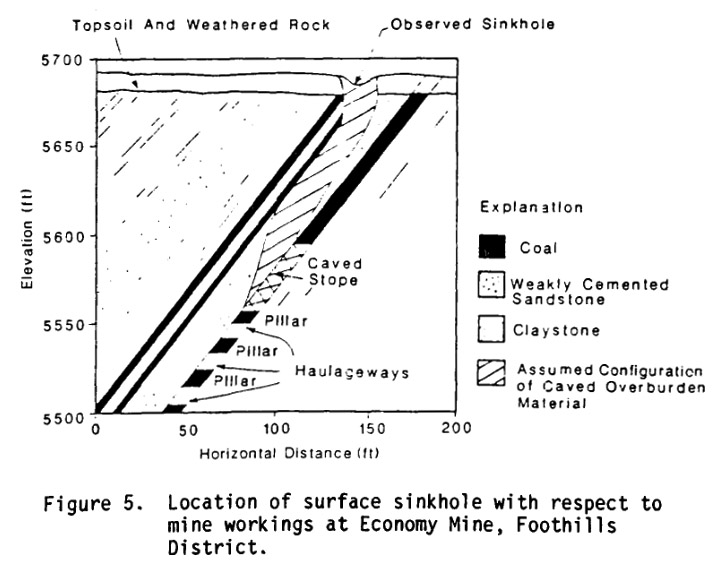

"Figure 5 presents an example of the relative location of the sinkhole development with respect to the mine workings for the Economy Mine in Littleton. As shown, the sinkhole developed up dip from the uppermost reaches of the stope. It is the authors' opinion that over steeply dipping coal mines (i.e., 50 to 80 degree dip), the roof collapses into the stope and the chimneying process progresses vertically upward until a resistant strata or very weak strata is encountered. Once a resistant or very weak strata is encountered the chimney process deflects up dip

and follows the bedding planes until it encounters the near surface weathered rock zone. At this point, the chimneying processes again continues vertically upward."

From p. 185 - "Proceedings of the 1985 Conference on Coal Mine Subsidence in the Rocky Mountain Region" - Colorado Geological Survey. |

Finally, in 2018, builders learned from some of the developer mistakes and the county reinforced road construction over the Unity / Economy Mine tunnels during the westward extension of Coal Mine Avenue.

According to a 9News

report: "an engineer with the county’s highway department, the portion of Coal Mine Road that travels over the historic mine is essentially built like a bridge, with extra steel and concrete that would support traffic were the ground underneath the road to collapse. When the county extended the roadway, the developer who owns the plot of land there put plans on hold for a neighborhood above the mine area, according to the same engineer, because of concerns about subsidence.

A golf course was built there instead.

A developer who currently owns the property did a survey of areas that may be susceptible to subsidence, the traffic engineer told us. Any area with risk will be back-filled with concrete to prevent a potential collapse."

After the extension was completed, developers were already eyeing the open field. Yet this time, before more homes went up adjacent to the mine, the developers performend an "in depth study" of the area and where subsidence was in evidence, they backfilled those areas and parts of the mine.

It seems recent builders are learning, but it remains to be seen if the latest construction efforts will last without any subsidence.

Nevertheless, with multiple subdivisions built near these trio of mines with extensive excavations, it is a matter of time before

an abrupt sinkhole or massive cave in known as a "chimney collapse" will occur. Hopefully, it won't, but as one employee of the Office of Surface Mining put it, "When you create a big hole in the ground, sooner or later it will come up and get you."

Coal mines have, and will, always be dangerous to operate and leave subterranean surprises.

Likewise, even the nearby Satanic Coal mine in Morrison claimed the lives of 6 miners to the same fire damp coal gas or asphyxiation due to carbon monoxide gas in 1921. In 1933, the same mine, after a raging fire built up gas, literally blew up, sending the massive, 60 foot high tipple 20 feet in the air and collapsed 40 feet around the obliterated concrete shaft. After the first disaster, the mine was named the Blue Bird mine, but after the second, it was closed permanently.

Again broad areas of subsidence remain in evidence at the site, and again, close to where new homes are being constructed.

Hopefully, coal mines will just become a part of the past and perhaps in the future, less destructive and less polluting sources of energy will again be embraced. It would definitely save everyone from any more troublesome mines and we all could breath more easily.

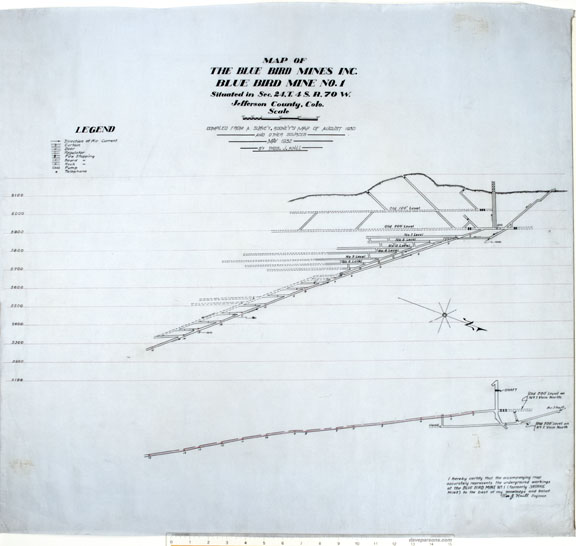

Original hand drawn 1932 technical schematic of the Blue Bird Coal Mine by Registered Engineer Thomas J. Knill. The mine which opened in 1872 was also the site of long buring underground fires which killed 6 miners and spectacularly blew up also from a buildup of gas from raging underground fires. Mine photo from Heritage Lakewood. Drawing from Parsons Collection (another timely discovery found on eBay, November, 2025 while writing this story) |

Despite the challenges of living with abandoned coal mines, sink holes, expansive soils, frost heave, cracking driveways and foundations, the geology along the Front Range still remains world class. Take a day, travel through time and hike through the amazing Fountain Formations at Roxborough State Park and Red Rocks Park as well as the hundreds of dinosaur tracks and trackways at Dinosaur Ridge and the huge fossil walls at the Triceratops Trail in Golden. Just avoid any sinkholes.

In a 1964 aerial photo, not much remains from the coal mines. Only a few coal stains and holes in the dirt in the middle of open farm fields along S. Kipling. The 1953 inset photo shows more coal staining at the Virginia Mine which all but disappeared in the 1964 photo.

Surprisingly, the Columbine Airport or Airpark, built about 1959, was on the high point on the corner of S. Kipling and W. Ken Caryl Ave.

The Colorado School of Mines Parachute Club, the Denver Sport Parachute Club and the Littleton and Evergreen Civil Air Patrol squadrons met here. Sky diving contests and numerous air shows also performend here before Columbine closed

around 1978 and was replaced by housing. USGS Earth Explorer photos |

The United States Department of Agriculture aerial photos from 1937 show the Unity/Economy and Virginia coal mines were still active and had numerous buildings. The Christensen Coal Mine had one structure standing and dirt roads entering the site. The surrounding area was still mostly open prairie and just a few agricultural fields. Photos from Aerial Photographs of Colorado, University of Colorado Boulder |

High temperature fire bricks found at the Unity / Economy mine in 1998. There were two variations of the Denver Fire Clay CO. (PDF) HIFIRE bricks, DESEPICO and GOLDEN fire bricks (PDF) and a number 2 fire brick. The number 1 brick was found at the Morrison lime kiln after it was demolished in the 1990s along with number 2 bricks. Fire bricks were used in Colorado mining primarily for lining furnaces and kilns, as they can withstand high temperatures and harsh environments. Fire bricks also offered excellent insulation properties and could have potentially lined the boilers and furnaces at both the Unity and Christensen coal mines. Boilers and furnaces were used to generate steam and heat, which were essential for powering equipment and providing warmth for workers in the mine shafts. They also helped in the mining process with drilling and transporting materials. |

Sources Used:

9 News

Coal Resources of the Denver and Cheyenne Basins Colorado - Colorado Geological Survey

Colorado Geologic Survey

Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection

Denver Public Library Digital Collections

Fossils - A Story of the Rocks and Their Record of Prehistoric Life by Harvey C. Markman

Geology of Colorado's Parks and Mounments by John L. Lufkin

Geology of the Littleton Quadrangle Jefferson, Douglas and Arapahoe Counties Colorado by Glenn R. Scott

Geology Underfoot Along Colorado's Front Range by Lon Abbott

and Terri Cook

A Guide to Triceratops Trail At Parfet Prehistoric Preserve by The Friends of Dinosaur Ridge

Heritage Lakewood

Jefferson County Historical Publications

Mining Catalogs – HAL’S LAMPPOST

Mountains and Plains - Denver's Geologic Setting - U.S. Department of the Interior Geological Survey

Roadside Geology of Colorado by Halka Chronic

University of Colorado Digital Library

USGS Earth Explorer

DP Home | Feature | Gallery | About

|