|

|

|

|

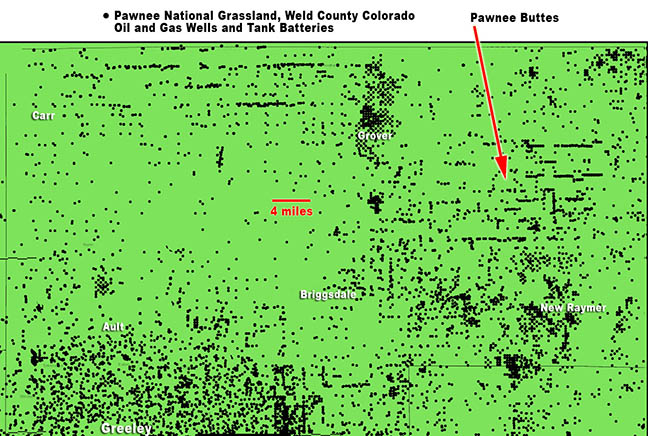

Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland May 22, 2020 Photos and text by Dave Parsons May 4, 2020 Dark streaks of rain lined the skies underneath the growing thunderheads. The wind was blowing so hard, I covered my face with my bandana and wore my buff to hold down my baseball hat. Underneath my boots, green shoots of short grass prairie colored the hillside in a light green as I wandered through the stout patches of prickly pear cactuses. Looking over miles and miles of grass covered plains, not a tree was in sight and a snow covered Longs Peak rose over the Front Range Rocky Mountains on the western horizon. As I approached my desired target near a windmill, a yellow Caterpillar road grader methodically gouged the nearby dirt road into shape, slowly churning and smoothing the rough washboard. Turning northward towards the distant Chalk Cliffs, grasshoppers jumped out of my way as I bent down to get a closer look at the half buried stones. Bright yellow flowers, tufts of grass and plump mountain ball cactus peeked out from between stones forming a circle, an ancient circle. With an ant hill and fire ring in the middle, a Native American tipi ring or as archaeologists call it ‘stone circle’ appeared. Another one poked out next to it and then walking a few paces another. Over thirty tipi rings buried to various depths in the soil wandered along the contours of the hill. Standing in the center of a ring about twenty feet in diameter, I could only imagine the wonderful desolation of the surrounding wilderness full of grazing bison with no roads, towns or cities. A fire crackled and sparked as your family relaxed around the glowing warmth with a thick rawhide covering overhead. A cold breeze blew at your lower back. Getting up and pushing the heavy leather flap out of the way you stepped into a raging blizzard and quickly pinned the edge of your tipi down with a softball sized boulder. I shivered just thinking about it. Strong winds buffeted me back to reality as I tried to avoid stepping on cactus. Those earlier people were made of tough stuff. I can hardly sleep on a comfy bunk encased in a metal cargo van. As for the cactus, I couldn’t imagine walking around in leather moccasins across a pincushion filled prairie. Some of the stone rings are from the last tribes to wander this patch of ground and some are thousands of years old. It’s easy to see early Native Americans tracking a herd of bison over the green hills or an Arapahoe or Cheyenne tribe setting up their camp. Heading back to my van, the ubiquitous white truck, support vehicles for the oil and gas industry streamed by in a virtual convoy on the newly graded road. Reaching the driver’s side door I was thankfully out of the wind and could hear myself think. Digging in my pockets for my Leatherman tool, I pulled the cactus spines out of my boots. There’s nothing worse than grabbing a sharp needle when getting ready for bed. Located in Weld County in northeast Colorado, the Pawnee National Grasslands are a 30 by 60 mile short grass prairie that was once considered a world class birding spot and quiet place to camp. Now, most people just drive by. Nothing to see except a couple of rock buttes. For many who once enjoyed these ‘public lands,’ they are now an industrial Mecca. They sit upon the massive Denver-Julesburg Basin oil and gas play and the mineral rights have been sold off by the Bureau of Land Management to the highest bidder. Companies from Texas and Colorado carved out well pads with batteries of storage tanks, drill rigs, flares, vapor combustors, pump jacks, pipelines and toxic ‘produced’ water basins which line the dirt roads. Oil industry even snugs up to the Pawnee Buttes, a wonderfully diverse geological formation with fossil bearing layers containing ice age animals and ancient sea creatures as well as nesting raptors. Finishing my lunch I rolled down a rutted dirt road and passed a parked SUV. Two young men, each armed with a long, black assault rifle, readied themselves to assault an innocent hillside. The road got rougher and the van sloshed back and forth. Finding a smoother track I headed back to the main road towards the Pawnee Buttes. Close to the road, a herd of pronghorn turned tail and ran towards the horizon. Hanging my 500mm out the window I rattled off a few photos while they sprinted away but realizing I was no threat, they slowed to a stop while cautiously looking back and started grazing again.

Passing another section of private land, a rancher had used an odd but useful fencing material. Old weathered oil rig drill bits poked out vertically from the soil wrapped lovingly with barbed wire. It was during the Dust Bowl days of the Great Depression in the 1930’s the Federal Government purchased land from bankrupt farmers and instituted soil conservation methods to restore the drought stricken, over plowed, over grazed and windblown land. Later, those marginal parcels of land became the Pawnee National Grassland in 1960. Managed by the Forest Service, the area is a checkerboard of private, State and experimental lands that are considered multiple use where everything from target shooting, grazing cattle, hiking and energy development occur. One informational sign off the road titled ‘The Power of Pawnee’ boasted of the wind energy, oil and gas extraction. ‘Multiple activities and uses abound… All around you are sources of energy. There is something for everyone to experience on the Pawnee National Grassland.’ Thinking of ‘National’ in any name, I think of National Parks like Rocky Mountain National Park or Mesa Verde. I don’t remember seeing burning gas flares or rows of storage tanks in the National Parks. Evaporation ponds, many larger than two football fields - over a dozen line the roads around the buttes alone. But these are ‘only’ the National Grasslands. Rolling eastward towards the buttes, flocks of black and white lark buntings, the Colorado State bird, clustered and flew in unison landing in fields or perching on the endless barbed wire fences. Blue-winged teals and mallard ducks paddled in pairs around shallow ponds made from the recent snow and rains. In previous years Wilson’s phalaropes, a colorful sandpiper-like bird would wade next to the ducks collecting insects off the surface of the water. No phalaropes this year. I hoped they escaped the many evaporation ponds which look so inviting to water loving birds.

For some of the 300 species on the grasslands they become coated with oil or ingest toxins from the water. According to a US Fish and Wildlife study, an estimated 500,000 to 1 million birds are killed each year across the country by oilfield wastewater disposal pits and facilities while thousands more are sickened each year. Outside the small town of Grover, an old, two story, wooded homestead stood against the wind with a wire clothes line still hanging in the backyard. Near this area in 2015, I discovered a family of swift foxes, tiny cat sized canines with amazing agility and lightning speed. Five pups chased tiny, flying, black beetles and ran from one den to another hiding in the tall grass until the parents came back. Adults carrying any food were quickly mobbed and relieved of their hard won meal. Stopping and searching today, there were no foxes to be found, but exponentially more oil and gas facilities. With my stomach grumbling again, I needed to find a place to make dinner and camp for the night. Driving to the top of a hill, a metal sign identified ‘Cedar Creek Wind Farm’ with hundreds of giant white wind turbines lined up along the ridges for miles. Passing an old wooden ‘Pawnee Buttes’ sign, I bounced along a rough, winding dirt road. I stopped at a junction in the road, pulled off and parked next to a fire ring filled with water and burnt wood cut up from signs and fence posts from the previous occupants. I angled the van so I could put the stove out of the wind. Pouring the water into a pot, the wind shifted and blew out the flame on the heavily shielded stove, twice. As dried prairie grass swirled and drifted into the open door, I managed to get dinner cooked and consumed. Cleaning up, the stove and fuel started sliding across the table as if an invisible hand was gently pushing them. Quickly, I scooped them up and put everything away while brushing the grass out of the van. Time to go for a hike, in the wind, an almost violent wind. On a previous visit, the conditions were much better. The scenery was much greener while hiking along the dirt trail along the base of the buttes. Armor plated and camouflaged desert short horned lizards warmed themselves on the sandstone rocks while big bumblebees bounced off the ends of newly sprouted wildflowers. Tonight though, brown, crispy grass left over from last year leaned in the wind bending towards the southeast. The sedimentary conglomerate buttes warmed in color as the sun sank towards the distant Rockies.

Wandering around, bending over and squatting in the wind and in general, looking like a bundled up drunkard stumbling through the prairie, I tried to find the the most appealing foreground while photographing the ever changing light on the buttes. I tried to shoot a little video, but the wind vibrated everything wildly. Shooting photos until sunset, I turned westward and photographed the glowing orb descending among the silhouetted towers of turbines. Walking back to my shelter, once again avoiding cactus, the rows of massive wind turbines lining the hillsides blinked red lights, strobing in unison like miles long strings of Christmas lights. Boots clear of cactus spines, I tried to relax as the shifting winds jarringly rocked the van. As night progressed the wind thankfully calmed a bit. Photographing here in previous years during the fracking boom, I recorded workers pulling night shifts on wells lit by blinding lights. Oil drill rigs and workover rigs hummed with activity as they worked through 4 a.m. fracking the Niobrara oil shale by drilling horizontally under the Pawnee Buttes. During mornings a light brown haze lingered over the area while viewed from the buttes overlook. Trying to drift into sleep, I read a book as the temperature dropped and wind calmed. May 5, 2020 28 degrees F this morning. I was expecting milder temperatures, but, welcome to ever changing Colorado! I slid the door open to the van expecting fresh air and - ooh, air I could taste. Never a good sign. Perhaps a little burning of agricultural fields with a hint of petroleum residue mixed in with a bit moisture. Yuk. I am reminded again not to stay too many days here. Residents living near oil and gas tank storage batteries in Colorado have been overcome by fumes emitted from venting tank hydrocarbons. According to one Weld county resident they “don’t even open the windows anymore” out of fear of health risks. Air pollution measurements made by scientists from airplanes over oil and gas operations in Weld County report emissions of 19.3 tons of methane per hour, 380 pounds per hour of benzene and 25 tons per hour of volatile organic compound emissions. All of these measurements are much greater than the oil industry has ‘self’ reported to the EPA. Despite Colorado adopting tougher capture rules (under heavy protest from oil and gas), toxins such as benzene and toluene emitted from leaks in oil infrastructure are still much higher than the oil industry reports. Increased levels of both benzene and toluene can irritate the eyes and skin and even the nervous system.

Keeping an eye out for my missing swift foxes, I occasionally rolled down the window to test the air. Eventually I hit pavement and enjoyed the quiet and smoothness of asphalt. I passed the mostly abandoned town of Keyota where a water tower looks out over the prairie dog towns that pop up with busy burrowing owls. Swainson’s hawk’s perched on the fence posts and walked in the grasslands like small feathered dinosaurs searching for grasshoppers. Finally the air smelled better and I pulled off the road near a prairie dog town. With a flash of white wings, a mountain plover vocalized and flew off near a den of prairie dogs. A pair of burrowing owls stood on a mound littered with shards of broken glass, chunks of plastic and wood dispersed among shattered bowls of clay pigeons.

Stealthily nibbling among the shrubs, a desert cottontail rabbit kept his ears lowered while staying close to cover. Also eating green plants this morning, a tiny, thirteen-lined ground squirrel, slinked low among the edible tufts. Following suit, I boiled some water for my oatmeal and pulled out my tripod. Taking bites in between photos, I watched a small herd of pronghorn walk close to the road with oil storage tanks and wind turbines rippling in distant heat waves. Brushing my teeth and cleaning up breakfast, I enjoyed the warm sun during a short period of calm and watched the pronghorn wander while listening to the birds chirp and prairie dogs bark. The wind picked up and pushed me eastwards as I followed the route of the 1887 Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad track, also known as the ‘Prairie Dog Special’ through what was left in the towns of Buckingham and New Raymer. Passing agricultural fields with dispersed homes and small town grain elevators, I crossed the invisible Texas-Montana Cattle Trail, part of the Goodnight-Loving trail that once traversed this region in the 1870’s. Looking around, I was standing in an amphitheater of sorts, surrounded by stone outcroppings, which gave a bit of shelter from the prevailing winds. Once again, dozens of tipi rings, mostly hidden from the untrained eye, remained nestled into the soil throughout the area. According to archaeologists and radiocarbon dating, the area had been long used by Native Americans, for over 2,500 years.

Pulling out my tripod, I set out to try and show the size of a tipi ring by adding myself to the photo. The problem was, so many of the ancient camp sites were so old and mostly buried under the prairie. In one area however, recent archaeological digs had found more recent evidence, with some rings dating as late as the mid 1800’s. Loading up a fanny pack with lunch, water and a camera, I shouldered the tripod and walked away from the van and quickly noticed three submerged rings just feet away from the dirt road. Striding across the grasslands, a huge flying grasshopper caught the wind and thumped me in the chest. Colorful butterflies, newly emerging, flitted over tiny flowers. Dried cow patties littered the area making it more difficult to see any potential rings. Next to an old group of tipi rings sitting low in the valley, high powered rifle shell casings sat gleaming in sun, their brass unblemished as if they had just sprung from the gun. .22 .38 and .44 caliber casings were pressed into the ruts of the dirt road. Recent fire rings with charred remains scarred scenic areas and more 4x4 tracks cut through the middle of ancient sites. Turkey vultures with outstretched wings slowly circled overhead as they coasted on the strong wind currents over the rocks. Walking back towards the van, I found a large, excavated circle with more exposed rocks. A few feet away was what I was searching for, a relatively undisturbed tipi ring visible above the grass. Setting up the tripod, I wandered around and around looking for the best angle, but the cow patties blended with the rocks and made the photo confusing. So, In the middle of nowhere, like a crazy person, I set out kicking, throwing, and prying out patties glued into the grass. Finally, the area mostly clear of cow made distractions, I set the self timer and walked around, squatted, touched the stones and played the role of model and photographer. Puffy white clouds started building shading the landscape and the temperature swung wildly between hot and cold. Driving down the hill, I found a more protected area out of the wind to camp at the base of the outcrop. Pulling out the binoculars, I slid the van door open, reclined in bed and did some bird watching. A pair of mourning doves cooed and flew short loops around each other. Rock wrens walked upside down, clinging to rocks, checking every nook and cranny for insects. Western kingbirds landed on the highest lookout only to spring up moments later snagging flying insects. Singing lark and chipping sparrows flitted about the boulders and shrubs. At dusk, young cottontail rabbits emerged from their dens under rocks. Spastically running from his den to the top of a rock, one young rabbit nibbled fresh green grass and eventually joined his roving gang of vegetarians.

As the clouds changed color at sunset I walked along the top of the rock outcrop and looked over the ancient landscape picturing in my mind a handful of native lodges dispersed on the landscape below. Like stone bird baths, eroded and rounded pockets of water remained on top of the ridges from recent snow and rain fall. The Pawnee Buttes were visible in the distance surrounded by silhouetted wind turbines as a half moon rose higher in the eastern sky. May 6, 2020 Further away from buttes, the air was cleaner this morning. As the sun crested the horizon, silhouetted pronghorn snorted and hissed, disapproving of my appearance. Another chilly 28 degrees as I walked around the van, checking for anything left behind as I ate my banana. Time for a morning game drive. Trotting parallel to me, the herd of pronghorn stopped and watched me slowly leave their valley. Driving past more lark buntings hunting along the road, I turned a corner towards Keyota past another trio of hawks, one rough legged and two Swainson’s just standing in a field. Stopping again at the prairie dog town, I pulled out the tripod and clicked on the long lens. With a flash of wings, a burrowing owl swooped low and came to a quick stop standing on top of his burrow. Turning his head to the left and the right, his yellow eyes scanned the prairie. Then like a piece of toast popping up, another owl popped up next to him. The pair flew back and forth over the prairie dog colony checking in at their various burros. The ever present pronghorn wandered over the grasslands.

Wanting to explore new territory, I headed west towards Briggsdale. Turning north on County Road 77, the route paralleled Crow Creek along an old Native American route which turned into the Trappers Trail of 1830 to Fort Laramie passing through Cheyenne, Wyoming. Driving past the Covid closed Crow Valley Recreation Area and campground, I followed the ‘Birding Loop’ signs onto Road 96. Slowing to a stop, I watched a nervous herd of pronghorn pacing back and forth. The herd was split up by a barbed wire fence. Pronghorn don’t jump over fences like the mule deer do, they shinny under a fence, scraping themselves through the lowest rung of barbed wire. Waiting for a moment, the herd all managed to organize on one side of the fence. More flocks of lark buntings, clay-colored, chipping, lark and savannah sparrows hunted in the grass and perched on barbed wire. Bullet hole filled signs at pullouts along the route gave information about various birds like burrowing owls or long billed curlews. The heavily washboarded road quickly turned into an undulating mess of routes and offshoots as parked 4x4’s dotted the landscape. Seeing spotting scopes next to vehicles, I stopped and pulled out the binoculars. No birds in sight, but plenty more rifles with scopes. Soon, trash littered the prairie and people shooting everything from handguns to hunting rifles spilled out over hills. A shooting range full of vehicles and people came into view. In the middle of the National Grasslands birding loop stood a recently constructed shooting range built with ‘critical support’ from numerous oil and gas companies as well as grants from Colorado Parks and Wildlife and the National Rifle Association. The self guided ‘birding loop’ makes a path around the Baker Draw Designated Shooting Area, littered with trash, clay pigeons, shell casings, shattered glass and destroyed targets despite signs stating ‘pack it in, pack it out.’ Rolling slowly down a severely washboarded road, I passed more bullet riddled birding signs. It’s hard to watch such an imperiled ecosystem and a rare hotspot of biodiversity degraded, polluted and trashed. Driving towards Greeley, I passed more and more storage tanks, flares and massive fracking drilling rigs located on ranches, farms and front yards. The Pawnee National Grassland is still an amazing place to visit, but It’s easy to see what takes priority in Colorado and the nation - but at what cost?

|

Destinations in the Gallery

All contents copyright ©Dave Parsons

DP Home | Feature | Gallery | About