|

|

|

|

|

Dust Bowl Days Search For Disappearing Lesser Prairie Chicken March - April, 2014 Written May 15, 2023 Photos and text by Dave Parsons Closing the air vents in my old Toyota truck, I passed the smelly cattle feed lots outside Lamar, Colorado. I watched the orange BNSF trains roll past in the opposite direction with huge farming implements standing in the agricultural fields like dormant, green dinosaurs. Near sunset, rows of massive GE wind turbines spun in the dimming light. Passing over the Colorado/Kansas state line just north of the town of Elkhart, I kept an eye out for any deer or wobbling porcupines out at dusk, now in the Cimarron National Grasslands. Turning off the highway, I slowed and clicked off my headlights. Braking to a stop, I let my eyes adjust to the darkness. Using just the yellow directional lights for illumination, I bounced down a rough, washboarded, dirt road as numerous kangaroo rats hopped through the ruts and into the scrub brush. Looking at the GPS, I was close to my destination. I found a turnout and parked, keeping the doors shut as the dust settled. Finding my headlamp with red light, I opened the door, stretched my legs and back and inhaled the cold, organically distinctive prairie air and then stood still, listening. Crickets and fan noise from nearby oil and gas pumping stations. Walking through the sandy dirt, keeping my light low, I saw the silhouetted outline of a small box against a rich, dark blue sky as stars began to fill the dark spaces. The cement and metal shack built by Andarko Petroleum was full of rodent droppings and broken window boards. The post apocalyptic looking building full of crap and dusty cobwebs hadn’t been used in years, at least not by humans. Not a good sign. Heading back through the sand sage and shrubs, a jack rabbit ran down the middle of the dirt road by the truck. Opening the door, I re-parked a distance away for the night ate and my spinach and pasta dinner at 7:30 pm and enjoyed watching the shooting stars and satellites in a rare, dark sky. Clear and cold, I rolled around in my zero degree sleeping bag in the bed of the truck after listening to coyotes yip and howl the entire night. In the morning after no sleep, I hatched myself out of my warm, down cocoon at 4 am. I pulled out the tripod and camera and took long exposures of the nearby windmill silhouetted against a star filled sky. There were no distinctive sounds made by any prairie chickens, just noisy fans. I donned my headlamp and packed up the camera gear and set up in the prairie tin can as wind rattled around the structure. Sitting on my fold-up tripod chair, I watched the horned larks and meadowlarks cheerfully sing all morning through the sunrise, but no lesser prairie chickens showed up. After repeatedly scanning the area with binoculars, I eventually headed back to the truck as another jackrabbit, or the same one zipped down the road. Driving back the way I came, I navigated a few miles away towards the "east blind," since the "west blind" near noisy oil and gas wells was a bust. Rolling over a rattling cattle guard, I unfortunately passed more oil pipelines, storage tanks and pumping stations and arrived at an actual parking area for the second, eastern viewing blind. Definitely in better condition, barely. The oil indicator on the dashboard looked low, so having just passed numerous well pads which fragment bird and wildlife habitat, I checked the engine dipstick and ironically added a half quart of oil to the old truck with mileage nearing 300,000 miles. During a late breakfast of spinach and oatmeal I watched the numerous horned larks chase each other while sitting on the tailgate. Tumbleweeds were stacked up along the barbed wire fence near the blind. Larks sang from the tops of yucca stalks. After watching birds, I did a bit of reading and took a short nap and then walked the dirt roads around the area. Dry, brittle grasses dominated the landscape with the occasional galvanized steel windmills in the distance. Towards the dry Cimarron River bed, leafless cottonwoods and poplars lined the sandy river bank. Another harrier hawk swooped low over the horizon. Towards dusk, coyotes began to yip as sandhill cranes vocalized, flying over the horizon probably towards the waters of the Platte River in Nebraska. The skies darkened as the remaining sunlight lit the dry grass, shining a bright yellow. A trio of white tailed deer walked the dirt road and inspected the fence line surrounding an oil pumper and out buildings as the northern harrier landed on a nearby fence post. Still no sounds from any displaying prairie chickens. Next morning was overcast, gray and dreary with high winds rocking the truck. Once again looking from the truck, I used binoculars to slowly sweep over the plains with no sign of life. Walking a short distance to the blind, I repeated the effort and listened intently. Again, just meadowlarks. Eventually, a narrow strip of orange marked the sunrise. Disappointed, I kept watch for another hour and again, nothing. Driving into the town of small railroad town of Elkhart passing the park and museum, I filled up with gas at the U-Pump’s antiquated and beat up, mechanical pumps with rolling black and white numbers as a lady disturbingly smoked her cigarette while also filling up. No pay at the pump here. After paying inside, I drove to the nearby National Grasslands government building as two dogs ran across the road in front of the truck. Any advances of the 21st century had clearly bypassed this town. Quizzing the coughing and candy eating employee, she informed me only one lesser prairie chicken arrived last April at the east blind and no birds had been at the west blind for years. In my mind, I grumbled at the online birding site that listed the disappointing Elkhart viewing areas. She continued to say, years of drought have resulted in a decrease in the birds. The drought had also closed the Colorado public viewing area at the Campo Lek for years, the whole reason I was visiting this area.

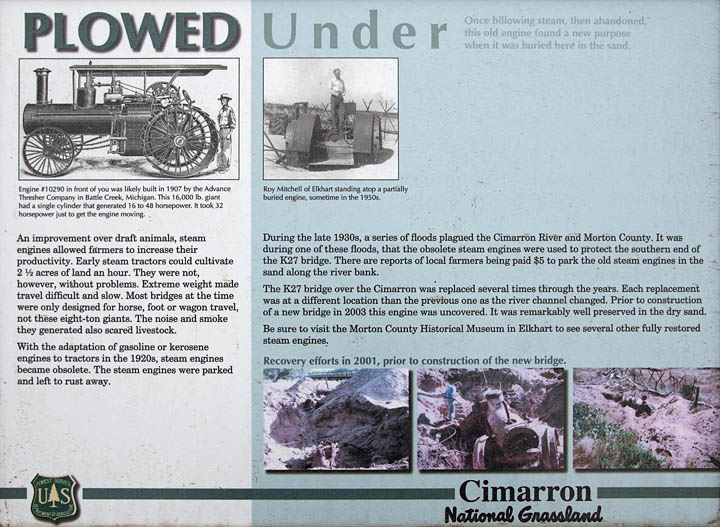

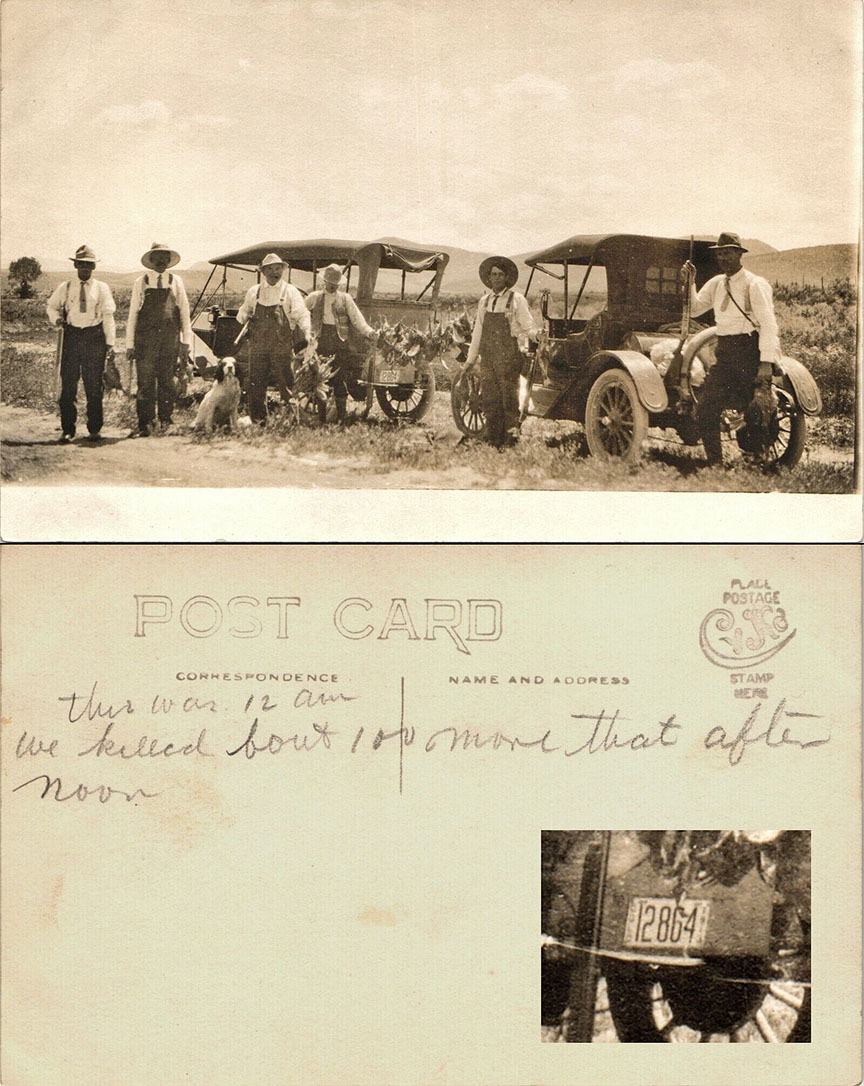

Snow was falling as I exited the office and drove back up Highway 27 back into the grasslands. Stopping at the Cottonwood Picnic Area along the Cimarron, I hiked along the dry river bed and through the nearby cottonwoods filled with lots of juncos, flickers, woodpeckers, and a pair of mockingbirds and the ever-present running of petroleum generators. A cloud of noisy red-winged blackbirds chirped and bounced their way northwards over the dry grasses. Two massive and rusty, eight ton steam tractors built in 1907 stood near the road where they were pulled out from the sandy river bottom in 2001 during new bridge construction. In an attempt to prevent erosion around the bridge, the obsolete and hulking tractors were "parked" in their sandy graves with reports from local farmers being paid $5 to do so. Newer and more nimble gas and kerosene fueled tractors replaced the old steam powered dinosaurs in the 1920’s. Unfortunately the improved tool also helped plow up millions of acres of prairie grasslands and help fuel one of the largest environmental disasters in human history, the Dust Bowl of the "dirty" 1930’s. The wind was howling and temperature dropped as I pulled into the Point of Rocks landmark area, again overlooking the non existent Cimarron River. The highest point in Kansas and along the Santa Fe Trail, the spot was also one of the first permanent settlements in the area. The landmark is also near where the Spanish explorer Francisco Coronado had passed during his 1541 expedition searching for his lost cities of gold. Driving Road 51 back into Colorado and the Comanche National Grasslands, I stopped and talked with a few curious horses loitering along the side of the road and passed by the Campo lesser prairie chicken viewing area, posted with "ROAD CLOSED" and a laminated printout of Forest Order Number 10-03 stating the "purpose for the closure is for resource protection of a special biological community" in effect from March 1, 2010 through May 31, 2015. Having struck out on this "chicken run," I resorted to exploring the history of the area and also getting a hike or two in.

Driving west from the closed lek, the sun started to peek out and the temperature warm. Soon I arrived at one of the many Santa Fe Trail routes, this one the Aubrey Cutoff, a shortcut from the "Mountain Route" starting at Fort Aubry in Kansas and running across the corner of Colorado and meeting with the more southerly Cimarron Route into New Mexico. Puffy white clouds zipped across a blue sky. Looking at the ruts in the dusty prairie, I pictured wagon trains of traders and settlers rolling across the vast grasslands sitting atop hard ass wooden seats inhaling dust and dirt while bouncing along the rough track and hoping to find a good source of drinking water. Between 1821 and 1880, thousands of wagons navigated the Trail, transporting fabrics and store goods from Missouri and returning from Santa Fe, New Mexico with furs, silver coins and mules. This was the early interstate highway system in old west with many more dangers than today's highways with every convenience available with just a turn of the steering wheel. Still determined to find any sign of the elusive birds, I drove east of the Campo lek area and bounced down a rough dirt "road" while still in the Grasslands and parked near an old windmill. Prairie chickens can be heard up to a mile away with their distinctive cackling and vocalizations, so If I couldn’t see them, perhaps I could hear them. Towards evening I set up a tripod and took time lapse photos of the clouds zooming by the windmill and kept an ear out. Walking the dusty road, yipping coyotes sang their family songs. Returning to the truck, I sat on the tailgate as the camera clicked away and ate dinner. As the sun descended behind the mountains, the temperature dropped and the sky cleared. Still, not any sign or sound of the prairie chicken.

Likewise, to see any remaining lesser prairie chickens in Colorado, I would have to pay $50 and resort to a 4:30 am meet up near the Kansas border at the town of Holly, Colorado to view the birds on private land a month later. En route to the location, I camped on the south side of John Martin Reservoir near Las Animas before the meeting. Night time extreme high winds literally lifted the truck body up with the wheels remaining on the ground and dropped it down with the shocks absorbing the jolt, all with me in a sleeping bag in the back. Needless to say, sleep was elusive as the truck violently jerked and shook for much of the night. Next morning in the dark, I met with a group of mostly birders at a roadside convenience store for a school bus ride to a farmer’s stubbly agricultural field where the birds were already cackling and sparring as the sun started to rise. Using the bus as a blind, the driver parked half a football field away from the performing birds. Binoculars and long lenses were the only way to really see what was happening. As a few photographers took photos, many of the other viewers were constantly talking, obscuring the odd sounds the birds made. The lek grew brighter and about seven males with a few females were cackling, strutting, stamping their feet, puffing up colorful air sacks, flutter jumping and chasing each other over the dry ground. It was a thrill to finally see. Unfortunately, video was not possible in the bus as viewers shook and rocked the entire bus as they shifted positions. The sun rose as we continued to watch and photograph, however some of the group grew board and restless and wished to go. I could have watched them all morning, however, the photographers negotiated only another 15 minutes of viewing. Patience, unfortunately, is not a common trait, especially in today’s era of short attention span. Furthermore, for some it seems, once a bird has seen, it can simply be checked off the list and its time to move on. I was there to see and document a rare species and enjoy watching the birds behavior, how they interacted with each other and the environment - albeit in an agricultural field.

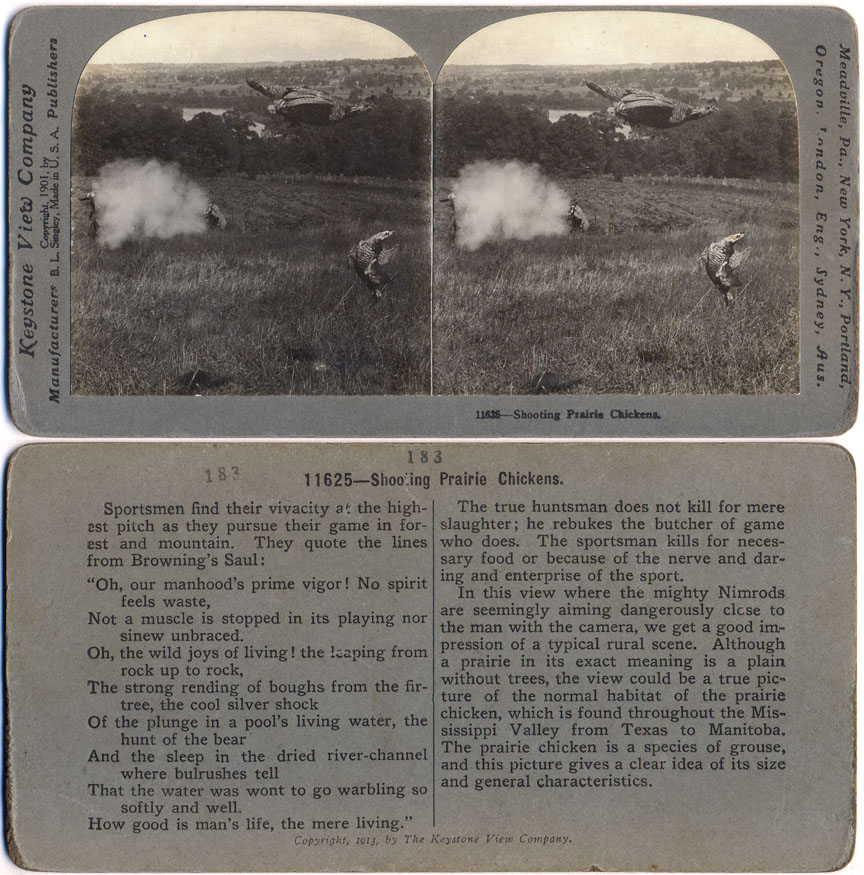

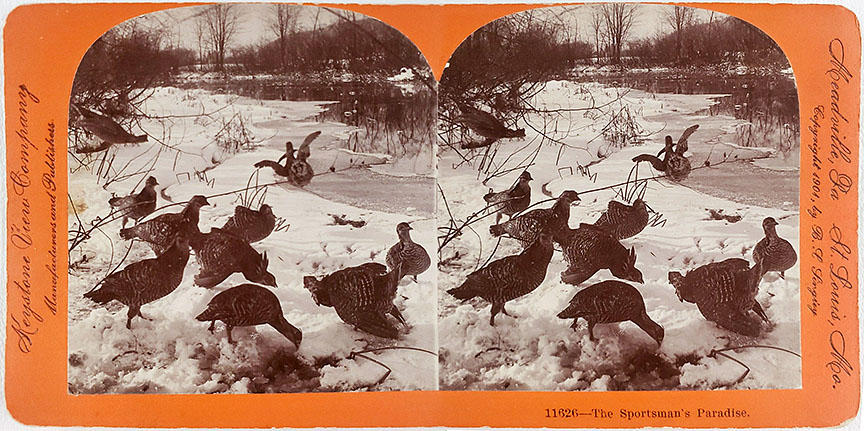

Lesser prairie chickens, roughly the size of domestic chickens and smaller than their cousins, the greater prairie chicken, depend on the sandsage prairie native in southeast Colorado and southwest Kansas. Its variety of short and mid-grasses, sagebrush and yucca, provide the birds with nesting and chick raising cover as well as food. In spring, March through May, the males display their courtship rituals on leks, also called booming or gobbling grounds. The male will bow deeply, droop his wings, raise the pinnae feathers on the sides of his neck and over their heads like horns and perform a dance with quick shuffling steps and stomping. Between fancy footwork, they will emit a gobbling sound by expanding the reddish air sacs on their necks, followed by a laughing cackle heard up to a mile away on calm days. The most dominant males occupy the center territory of a lek and do most of the breeding. The females will wander the lek, nibble at snacks and watch the action, and perhaps select a male. At times, males will trespass on each others territories and brief fights will occur as they take to the air and charge each other with legs outstretched. Feathers will fly, but the confrontations are more bluff than battle. They perform at sunrise and sunset, however the evenings are not as intense.

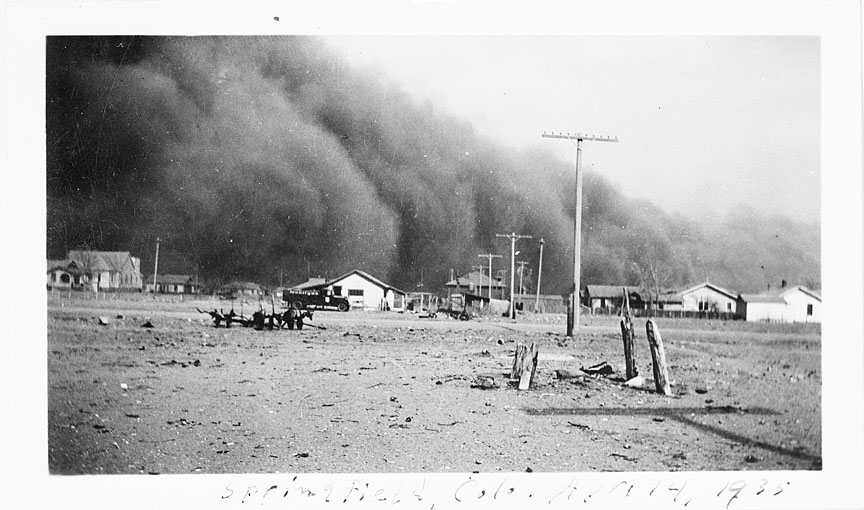

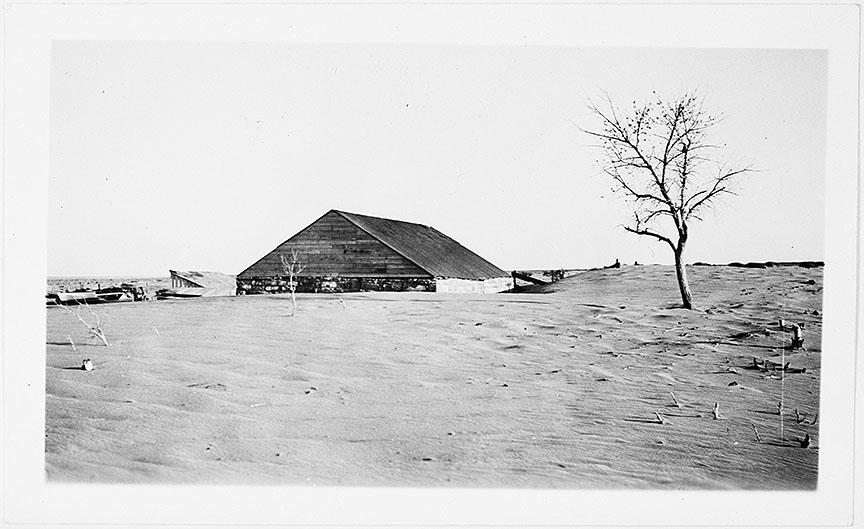

Pecking at the ground like a domestic chicken, they feed on insects, seeds, grains, buds and leaves. About every predator enjoys a meal of prairie chicken. Coyotes, hawks, eagles regularly hunt and flush the birds from their leks and skunks can devour their eggs. With a lifespan of one to five years, the females lay 11 to 13 creamy or buff colored eggs in a grass lined depression, usually under a shrub. Overgrazing by cattle and removal of sagebrush and yucca for agriculture has degraded much of the habitat to a point that it cannot support the species. Years of drought has exacerbated the problem. Furthermore, limiting their range even more, according to Kansas researchers, lesser prairie chickens "will not nest withing 300-400 yards of center point irrigation equipment or within 200 yards of oil and gas wellheads, 400 yards of power lines, 860 yards of improved roads, or 1,370 yards of large structures such as wind towers." (Save The Last Dance - The Story of North American Grassland Grouse p. 70) Likewise, it should have been no surprise that there were zero birds near the Cimarron viewing blinds with so many dirt roads and noisy oil and gas infrastructure so close by. Ironically, the decline of the grassland habitat for the lesser prairie chicken continues today despite decades of federal efforts to restore the over plowed and eroded lands. The initial grasslands disaster started during years with high rainfall as misguided farmers, sod busters and out-of-state speculators or "suitcase famers" looking to capitalize on high wheat prices during WWI, ploughed huge tracts of marginal lands unsuitable for dry farming in the arid west also known as a high desert. With the help of the new and improved tractor, plains that were once covered with grasses that held a fine topsoil in place and provided wildlife habitat were quickly exhausted and over grazed by cattle and sheep herds. As the weather turned dry, farmers were ill prepared for eight consecutive years of drought. The parched lands shriveled as settlers stripped the plant cover and grasses creating disastrous conditions as massive wind storms repeatedly carried top soil across the country during terrestrial tidal waves of "black blizzards," dust storms so thick, they turned day into night. One witness from the panhandle of Oklahoma wrote in her book Leave It To Miss Annie: "The sky would darken and heavy black billowing clouds of dust would approach like a huge wall that boiled and crumbled as it advanced, burying crops and producing almost total darkness. To go from house to house, it was necessary to wear a dust mask and carry a flashlight. Sometimes the wind was so strong one could scarcely advance in the face of it…" Massive amounts of static electricity would pass through the storms, shorting out vehicles as people were driving, stranding many on the road in the heart of a storm. Drivers resorted to dragging chains for grounding their vehicles. Barbed wire fences and anything metal would be charged and jolt anyone who touched them.

From 1934 to 1936, about five million acres of land were blowing away and during 1937 alone, there were 72 such storms. As the soil disappeared, so did the settlers as farms and ranches which were abandoned or foreclosed on, resulting in the largest migration in American history with 2.5 million people moving out of the plains states by 1940. As the Depression struck another blow, by 1935 in some counties, 80% of the families were living on government relief.

Congress realized strong measures were required to repair the land and help its residents. In 1933 and 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Industrial Act and Emergency Relief Appropriations Act which gave the Federal Government authority to purchase failed croplands. With these and other New Deal programs, thousands of farms were purchased and retired from cultivation and families settled elsewhere providing economic relief to many. Furthermore, starting in 1937, over 10 million acres encompassing today’s Comanche and Cimarron National Grasslands were set aside removing the degraded croplands from production with 2.6 million of those acres being purchased by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Later, the land, under various management schemes would eventually become multi-use under the U.S. Forest Service and again, squeezing the prairie for every resource with grazing lands for cattle, wide spread oil and gas extraction with its accompanying crisscross road system and open space for wildlife and recreation.

Unfortunately, the dusty history is repeating itself as long stretches of drought continue today, exacerbated by climate change, over grazing and ignored soil conservation measures such as contour furrowing, reseeding, planting shelter belts and no till farming. Compounding the issue, water use is intensifying as the heat increases. Under the grasslands, the Ogalala Aquifer, which supplies over 2 million people of drinking water, is being over-pumped and polluted to support thirsty crops. The nearby Arkansas River is reduced to a trickle as irrigation struggles to support agriculture in the Great American Desert. For 42 months before 2014, the National Weather Service reported parts of all four states received less rain than a similar period of the 1930s. According to an old-timer in the panhandle of Oklahoma, "When people ask me if we'll have a Dust Bowl again, I tell them we're having one now," said Millard Fowler, a centenarian in 2014. "It is just as dry now as it was then, maybe even drier. There are going to be a lot of people out here going broke."

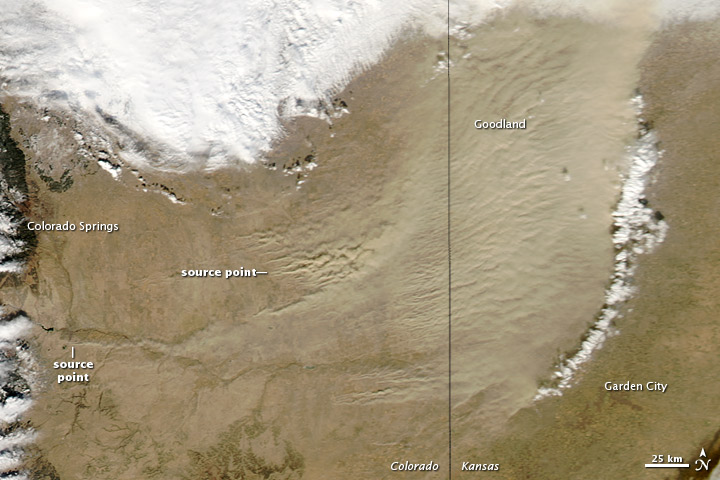

Likewise, massive dust storms have again swept across southeast Colorado into Kansas and neighboring states. As wind whips up sand storms like the Dust Bowl days, the blowing walls of dirt have been visible from satellite imagery with their sources in overgrazed Colorado lands with open agricultural fields once affected during the 1930s. Like a giant bullseye, the junction of Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, the epicenter of the Dirty 30’s is also the center of many of todays drought and dust plagued sand storms. In addition, as short grasses and soil are over grazed and depleted, many evasive plant species proliferate including Russian knapweed, deadly to horses and Russian thistle with its troublesome spiny tumbleweeds that spread thousands of seeds from one plant. During high winds, huge piles of packed tumbleweeds roll across the landscape clogging fence lines, gates, blocking roads and even stacking up around and over buildings.

Still parked in the Comanche National Grasslands under a ever present water pumping windmill, the next morning was cold as I crawled out the back of the truck. No sign or sound of chickens. At least it was not snowing. The sun was up as I rolled down the washboarded dirt and dust while looking forward to a paved highway. Nearing the wondrously smooth asphalt, I stopped for a few photos of a road runner perched in a dead tree. With gas stations few and far between on the grasslands, I stopped to top off the gas tank at the town of Campo and was impressed by the even worse condition of the pumps than those antiques in Elko. Semi trucks continuously lumbered up and down the highway past the station, their rumbling heaviness reverberating in my ribs as I thought to myself, I would not like to live near here. As I left the luxury of the smooth pavement for more bowel bouncing ruts, dirt and washboard and took Road 116 towards the Purgatoire River and Picketwire Canyon to hike the 150 million year old dinosaur trackway, the largest in North America. Rolling over numerous clanking cattle guards, I passed by another branch of the Santa Fe Trail, the Barlow and Sanderson mail and stage route which once provided regular scheduled mail and passenger services between Las Animas and Trinidad along the Santa Fe Trail before the railroad was established. The trail, located just southwest of Vogel Canyon was last used around 1880 when rails finally reached Santa Fe, ending the use of the longtime stage coach route. Previously, for thousands of years, Native Americans lived and hunted these wide open, dry, windy, short grass prairies, living in natural balance with a robust ecosystem. The following European expansion and the introduction of Spanish horses set into motion a fire that spread across the continent as the Spanish pushed in from Mexico and the English from the East Coast. Native tribes were displaced and pressured to move from their original homelands. The cascading effect pushed the Comanche, Kiowa, Kiowa Apache, Cheyenne and Arapahoe tribes into Colorado and nearby states where they traded with incoming Europeans while hunting the herds of bison. American exploratory expeditions also ventured into the territory and in 1820, as a group traveled through the massive grasslands, a Major Stephen Long announced his distaste for the area and declared "I do not hesitate in giving the opinion that it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable" and proceeded to label it on his map "The Great American Desert." Trade routes through the area were established following earlier Native American thoroughfares, and in the same year, the Santa Fe Trail opened to travelers with thousands of wagon trains crossing the arid territory between 1821 and 1880.

Back on the road, I passed the turnoff to Vogel Canyon, a tributary of the Purgatoire River where springs on the canyon floor supported wildlife and early Native Americans. I turned left at a junction with a green and bullet riddled Rd 25 sign standing next to another brown sign pointing the way to PICKETWIRE CANYONLAND, 6 MILES. Rolling through bending arroyos I passed the lonely, cholla cactus filled Picket Wire Corrals, still in the Comanche National Grassland. The scenery transitioned from open prairie with wandering herds of pronghorn into a mixed grassland and pinyon juniper landscape. The area also hosts the occasional abandoned stone and adobe farm or ranch building which would disintegrate and crumble to dust behind a screen of junipers or tall grass as it slowly absorbed back into the earth. Native American petroglyphs from local tribes and earlier hunter gatherers thousands of years ago remain pecked into sandstone boulders that have tumbled down from the canyon walls. The road narrowed to a rough and narrow two track weaving through the prickly pear cactus, juniper trees and yucca plants. Arriving at the Withers Canyon Trailhead and camp ground, I pulled into a spot and prepared for my descent into the canyon. Hoisting my water, pack and camera gear over my shoulders, I hiked down the rocky canyon into the Purgatoire River valley where an old two track road was lined with old rotting telephone poles with clear glass insulators still perched on their wooden posts and a couple of downed lines of rusty wire. Early stone and adobe homestead remains melted into the valley floor. Abstract petroglyphs of squiggly lines and others of deer and bighorn adorned many of the hidden spots on nearby boulders. Looking over the tall grass, a coyote tracked my movement before disappearing into the trees, likely hunting for the numerous cottontail and jack rabbits. During the summer months, Colorado checkered whiptail and eastern fence lizards patrolled the rocky canyon walls as orange and black checked variegated fritillary butterflies and giant tarantula hawk wasps enjoyed flowers and broadleaf milkweed blossoms. Iridescent green spotted tiger beetles and two-tone yellow and green racer snakes hunted the sandy trails. Camouflaged Woodhouse toads with bulging eyes enjoy the moist areas near the river. In the fall, male Oklahoma tarantulas come out of hiding en masse and search for females. The Purgatoire River is fed by the snows of the Sangre De Cristo mountain range to the west and meanders northeast 175 miles across the Colorado plains and merges with the Arkansas River at the town of Las Animas. According to legend, the river was thought to be named by early treasure seeking Spanish explorers in the 16th century who died in the canyons without any clergy performing last rites, thus leaving their souls wandering purgatory. The resulting name was "El Rio de Las Animas Perdidas en Purgatorio," or the River of Souls Lost in Purgatory. Later, French trappers shortened the name to "the Purgatoire" and the following early Anglo travelers on the Santa Fe trail who could not pronounce "Purgatoire" and simply mangled the name, calling it "Picketwire."

Continuing down the sandy road bordered by tall grass, I passed the dilapidated ruins of the late 1800s Catholic Dolores Mission and surrounding cemetery with a few decorated headstones, containing graves of mostly young children from Hispanic settlers who had died in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Hiking a couple of miles further along the dirt road as it parallels the wandering river, I encountered the Jurassic dinosaur trackways made 150 million years ago in the river eroded Morrison formation. The area was once a tropical forest with sequoia trees and ferns along the shoreline of a massive lake where many dinosaurs like Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus and Diplodocus walked in the soft mud. Their deep tracks were preserved by rising water levels where additional mud layers were deposited and eventually, over the millennia hardened into limestone. Their skeletons are also preserved in nearby layers and have been excavated from the canyon walls surrounding the trackway. Over 1600 footprints from 120 individual dinosaurs have been exposed and demonstrate how dinosaurs moved; running or walking in herds or leading solitary lives. After inspecting three toed Allosaurus tracks, I jumped from boulder to boulder and crossed the river to explore the parallel sauropod trackways exposed in the rock. Piles of logs and debris were cleared from the tracks and areas had been excavated exposing new tracks.

Photographing the trackways, I appreciated the recent snowfall melting in the track depressions which made them more visible in the late morning sun. Returning to the road, I headed towards the nearby boulders and explored the more recent human history, a variety of 1000 year old petroglyphs pecked into nearby canyon rockfalls. One set of interesting petroglyphs was located on top of a boulder and seemed to represent a

Waking up to a warm morning was quite a change from a couple of days earlier with its snow and freezing temps. After breakfast, I was back on the dirt Road 25, bordered with barbed wire fences heading north while rolling past herds of pronghorn. Turning west on N Road, I eventually encountered coveted pavement. Hanging a left onto Highway 350, I passed more Santa Fe Trail crossings, desolate farms and the abandoned "One Stop" store in the town of Delhi, a lonely spot with a series of shacks and wooden buildings in various stages of decomposition. Soon, a military tank was visible on the side of the road, marking my next area to explore. Turning into the U.S. Army’s Fort Carson Pinyon Canyon Maneuver Site, I checked in at the Cantonment Area, entering my valid permit number into the troublesome computer. The Army maneuver site, located adjacent to the Purgatoire River and Picket Wire Canyonlands allows hiking, hunting and camping in areas where and when they are not preparing for WWIII with thousands of soldiers, and hundreds of vehicles including helicopters, Humvees, Bradley fighting vehicles, Abrams tanks, assault vehicles and more during massive training maneuvers.

Driving past the Small Arms Area firing ranges, I headed into the central part of the site. Some of the dirt roads disappeared into arroyos and some were nicely graded and graveled. Some led to old decayed homesteads now occupied only with small critters and perhaps an owl or two. Heading down a tributary of the Purgitoire River, an area called the Black Hills, I hiked through small sandstone canyons with ancient Native American shelters and grinding stones on boulders, still smooth with use. Close by, remains of settlers homes were now rectangular and collapsed stone foundations. Arroyos still had water remaining from meltwater or springs, good for potential wildlife sightings. Later, I stopped to photograph a ranch marked on an old PCMS Hunting Map as the "Cross Homestead." The site was a collection of adobe, stone and railroad tie constructed buildings nestled in the mouth of a small canyon. Rusty pipe and juniper/pinyon log corrals leaned dangerously to a point of collapse and were backed up against the sandstone canyon walls. Next to a dilapidated, wooden and adobe home, an old windmill tower topped with only with a tail stood next to a large, galvanized steel water tank perched on a square cabin of railroad ties. Dry grass and barbed wire fences surrounded the outpost with a dry check dam reservoir and Lockwood Arroyo in the front pasture. After a day hiking and exploring, the only wildlife I encountered were hawks and larks - and not one person. On the way out I drove past the shooting ranges, fake city block complete with buildings, cars and motorcycles and checked out at the entrance.

Nearing Interstate 25, I passed the small hole in the wall "town" of Tyrone, another series of abandoned farms shacks with a windmill tower converted to an antenna. Tumbleweeds were overflowing a barbed wire fence and climbing up to the roof of an adobe building. Closer to Trinidad, the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe trail crossed the highway. In Trinidad, the sky darkened and the rain began to fall. Driving north on I-25, rain changed to snow, and then to a literal blizzard. Bumper to bumper vehicles collided in front of me with bits flying, slapping each other and spinning on Monument Hill just north of Colorado Springs. Quickly deciding to get off the highway, I pulled over at the Greenland exit, got out in the wet, pelting snow, turned the hub locks on the front wheels for four-wheel-drive and took the slow route home on Highway 105 as the snow quickly deepened. |

All contents copyright ©Dave Parsons

DP Home | Feature | Gallery | About